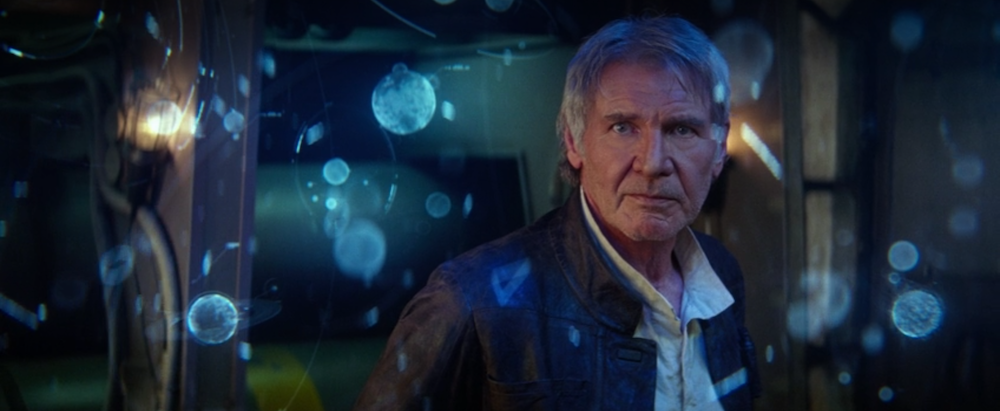

Han Solo’s remarks in The Force Awakens (2015) about the true existence of the Force and Jedi signal an interplay between canonical and non-canonical material that taps into an even broader concern over authority and canonicity among traditions outside of the Star Wars universe – in particular, the world’s religions.

Han Solo’s confessional remarks in The Force Awakens (2015) about the true existence of the Force and the Jedi – all of it – aren’t just an exciting assurance to Rey and Finn about repressed hope in the galaxy; they also signal a broader interplay between canonical and non-canonical material that has preoccupied the franchise’s fandom since the release of A New Hope (1977) over forty years ago. They also tap into an even broader concern over authority and canonicity among traditions outside of the Star Wars universe – in particular, the world’s religions.

Having just finished a section of my dissertation on canonicity and adaptation, I had been looking forward to presenting some thoughts I’ve had at the intersection of these topics and popular cultural examples at a conference back in March. Star Wars was an obvious choice when the panel was being organized – not just because the impending release of The Rise of Skywalker (2019) was on my mind, that I’ve been a fan for most of my life, or that Star Wars itself is a product of explicit sampling, remixing, and cultural citation (see Kirby Ferguson’s breakdown of this in part two of “Everything is a Remix,” at about 3:15), but because it has always narratively engaged issues surrounding canonical formation and maintenance.

Unfortunately, the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 around the world this past season prevented many scholars from sharing their research with peers and colleagues – myself and those on the panel included – so I figured I’d briefly do some of that here instead.

One of the perspectives I’ve taken in my work – in a sort of mashup between Eduardo Navas’ “Framework of Culture” and the dialectic relationship between humans and society famously put forward by Peter L. Berger – is the reframing of religious traditions as cultural constructs that engage with particular content in archival spaces, sampling and remixing what has been legitimated as acceptable material in their respective databases as they develop and evolve. In brief, legitimated iterations of traditions (schools, sects, denominations, or the like) can be understood as accessing and mixing such content to suit their unique nature and needs. That remixed content might then be recycled back into the archive, providing future – or current – iterations with additional and legitimate creative fodder for further repurposing.

These types of sampling processes can be observed in the narratives of contemporary religious traditions, which are often the ambiguous products of oral transmissions that occurred over many years, in many different places and forms, and for varying purposes. And just as their success hinges upon their reception among adherents, popular cultural storytelling must capture its fandoms with an alluring array of narrative features that keep them intrigued, wanting to learn more, and able to uniquely identify with as the stories grow and expand in different contexts.

Getting back to Captain Solo’s remarks, however, judging the veracity of such stories – in both explicitly religious and popular cultural contexts – largely depends on your point of view. But officially, in the case of Star Wars, they’re not exactly all true anymore. While there was a time when this was sort of the case, to a greater or lesser degree, when Disney became the proud new parent of Lucasfilm, everything changed.

What had once been considered the Expanded Universe in Star Wars media became re-designated as Legends shortly after the acquisition, creating a Canon-Legends divide that resulted in not just a rebranding of previous, expanded narrative content, but alternative repositories of Star Wars timelines and data. Even the famed Star Wars wiki, Wookiepedia, maintains two parallel directories for Canon and Legends material. The former is official and the latter is not – at least not according to the newly established Lucasfilm Story Group tasked with maintaining the new continuity of canonical material.

But how did those of us who have been immersed in the Expanded Universe since the release of the first film trilogy take this? Did official status shift the way narrative content, backstories, and planetary histories – the type of world-building science fiction fans adore – were understood?

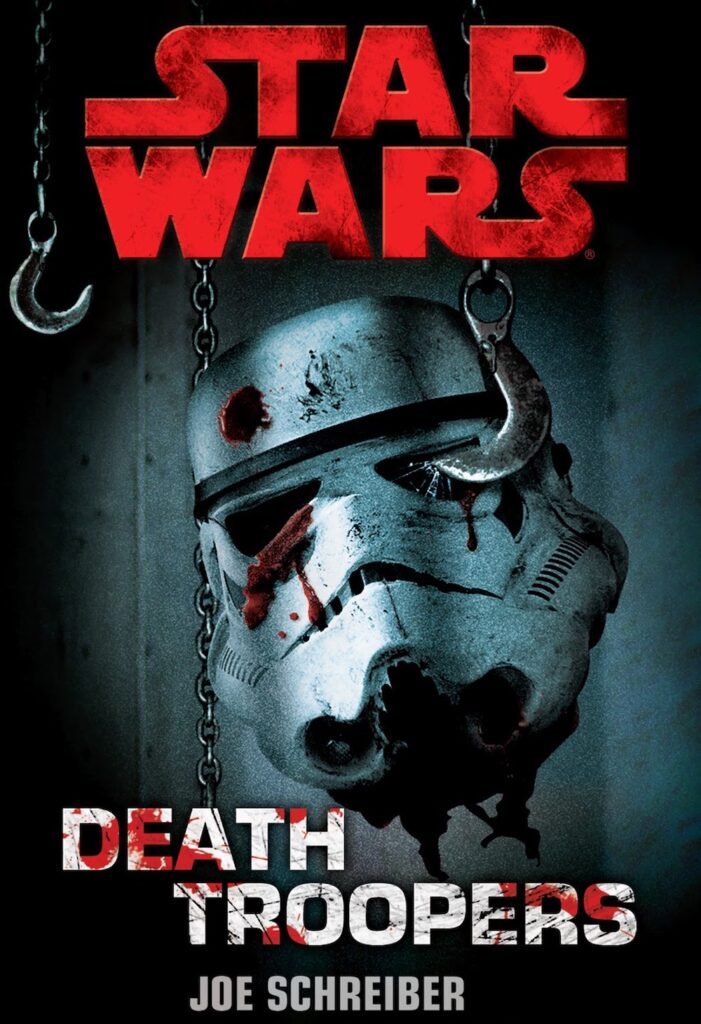

The short answer is not really. The notion of a single, cohesive narrative continuity has probably been a welcome prospect for many fans, but there’s just so much material that we have grown to love and already accept that makes this shift a rather difficult one to embrace – and it’s been over five years since that new continuity was established! I mean, how can I possibly be expected to disregard the horrifying zombie crew of the derelict Star Destroyer in Joe Schreiber’s Death Troopers (2009) just because Disney’s new taskforce didn’t give it the stamp of approval?

The point is, even though it’s no longer officially part of Star Wars canon, Legends material – especially when it doesn’t directly contradict the new Canon – is still generally accepted and enthusiastically engaged among fans.

And Disney.

Legends material hasn’t exactly been pushed to the Unknown Regions of popular culture and forgotten about entirely. Ongoing websites like The Expanded Universe certainly attest to that. It might be better to think of it as being more so scrapped for parts, sitting diligently somewhere along the popular cultural Outer Rim, awaiting to be repurposed by new caretakers. In other words, Disney uses its discretion to pull from de-canonized Legends material in order to create new canonical material (the reintroduction of the popular Grand Admiral Thrawn is a great example). While Legends material is now considered unauthorized – “excommunicated,” so to speak, by Disney after it acquired the franchise – the creation of authorized and canonical material can be done so from this unauthorized space in either remixed or strictly sampled formats. Disney could technically, and simply, just re-establish something in Legends as canon, much as it previously, and simply, dissolved it, which would mean that non-canonical material could all of a sudden regain that designation.

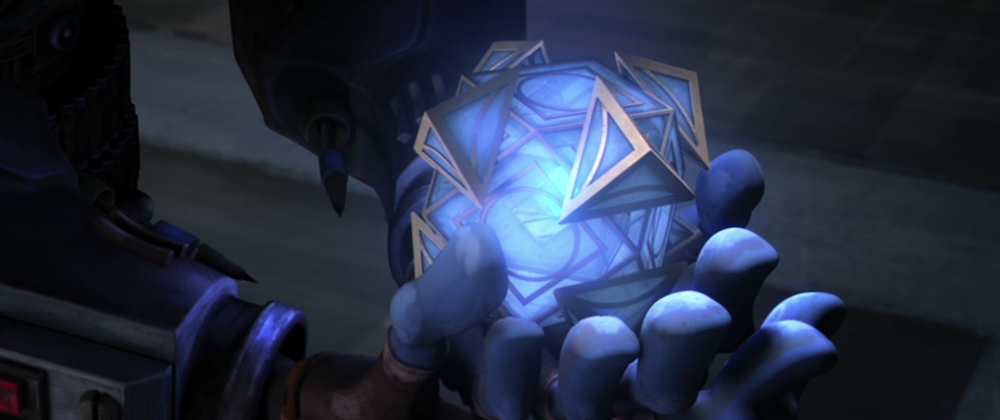

This pattern of repurposing content follows a trend in Star Wars media that existed well before Disney’s acquisition, too. The animated Clone Wars series has done this, for example; certain elements in the prequel film trilogy, like the galactic capital being on Coruscant, were pulled from expanded media as well. Content in both the main Star Wars films and what was featured across various media have always been in dialogue with each other. Formerly, it was all organized in a complex canonical hierarchy, or Holocron – much like the in-universe enigmatic repositories of knowledge and wisdom – and maintained by a Lucasfilm “Keeper.” It’s a little bit more straightforward now with that cohesive continuity in mind: all officially licensed Star Wars material created since the acquisition has been and will be considered the same level of canon.

The sampling processes found across religious traditions and their narratives both parallel and differ from what is taking place across Disney’s Canon-Legends divide: while an explicit sampling of source material from the Legends archive might be occurring, rather than such material being already inherently authorized in a common archival space officially available for accessing and uniquely remixing, it is only made authentic as it moves from an unauthorized space to an official one. In other words, and in a way far more organizationally balanced than what might be found among other cultural traditions, two spaces reminiscently exist in a balanced continuum of creative forces – between the validated and the prospective, between legitimacy and the struggle to remain in power.

Ironically, creators who contributed the now unauthorized expanded media content to the Star Wars universe in the past – in either novel, graphic, gaming, or televised media (Star Wars is truly a transmedia exemplar) – have also indirectly provided Disney with a vast archive of source material from which to sample and re-authorize, and implicitly shaped the narrative choices the Lucasfilm Story Group is making in its developments (not that new material can’t also be created, of course). Authoritative structures might determine what is official in both popular cultural franchises and in religious traditions, but it is important to consider how such content is actually measured and what sorts of variables guide the selection and use of that archival material – especially since what is official might not always align with what is accepted.

One of the main reasons Legends material is still favored among fans has to do with how they received that material in its originating contexts. Even amid the newly-developed storylines and characters of the recent film trilogy, the remixed elements that the Lucasfilm Story Group sourced from that alternative database can be recognized: Ben Skywalker was Luke and Mara Jade’s son, raised off and on by Han and Leia while they raised their own three children – one of whom, Jacen, eventually turned to the dark side, later to be killed by his twin sister, Jaina (but not before he killed his aunt, Mara Jade), with their other son, Anakin, constantly plagued by his namesake’s dark legacy; Palpatine was able to survive his spectacular fall in Return of the Jedi (1983); and a crumbled Imperial force arose in opposition to the New Republic.

The principles guiding the recyclability of culture are not haphazard; content is selectively repurposed because it has functional value in its applied contexts. Having a character like Ben Solo hauntingly dazzled by his grandfather’s darkness, killing one of his own parents, while navigating a different sort of dyadic and intimate connection with another (who delivers a mortal blow to him even though it is later rescinded), is perhaps a cleaner way of incorporating the narrative elements that already existed in Star Wars media. Those devices had already been accepted among fans. They worked in the past, which is why they were selectively reworked in the new continuity.

Of course, authoritative structures – various religious functionaries and Holocron Keepers – play crucial roles in those official and determinative processes of selectivity, which is why matters of legitimacy and authenticity often accompany considerations of success and acceptability. And, as history demonstrates, the relationships between those notions are hardly ever unequivocal or consistently aligned.

The re-canonization practices in contemporary Star Wars media offer some insight into how authorized choices are guided by certain power dynamics. And although they might specifically pertain to material in a galaxy far, far away, they suggest some of the broader issues accompanying canonicity, its establishment, and its maintenance among religious traditions as well.

Cultural traditions are predicated upon shared repositories of knowledge and wisdom – their own unique Holocrons of archival data that situationally shape and enable them to adapt to new contexts. It’s not so much a question, then, of whether all of it is true, but a question of what that all comprises, how it is determined, and who is in charge of making the decisions related to its maintenance. Put another way: one’s certain point of view doesn’t determine truth per se. Those “truths we cling to” might “depend greatly on our own point of view,” as Obi-Wan Kenobi so cleverly reasons, but they are also the result of the legitimated structures that precede them.

Images from Return of the Jedi and The Force Awakens via Lucasfilm Ltd. 1983 and 2015. Image from Star Wars: The Clone Wars via Lucasfilm Animation 2009.