Buddhist teachings on attachment and desire can help us understand the widespread reluctance to accept and embrace societal changes during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Cases of SARS-CoV-2 continue to rise across the United States. The deaths associated with them haven’t relented either. Places that have remained far too carefree with their preventative regulations and procedures, along with those that were arguably too quick to re-open their cities in the wake of shutdowns, lock-downs, and stay-at-home orders, haven’t helped the situation either. And now we’re facing another period of uncertainty amid re-closings, mask orders, and probable waves of new and repeated layoffs to bog down a relief system already in turmoil: the back-to-school season of late summer and early autumn.

One of the things that became clear to me during the pandemic’s initial spread earlier this year was how mind-boggling the reluctance to take drastic precautions was across the country. Sure, shutdowns and closures occurred, but it was mostly in the form of baby steps than it was out of a realistic drive to get ahead of this thing. The federal government is rightfully blamed for botching palliative and preventative programs, and state leaders following its lead have equally contributed to the devastation that followed. It doesn’t help having an administration refusing to wear a mask or properly distance from others, downplaying the severity of the situation, confusingly at odds with scientific data, feeding into the conspiracy theories and ignorance throughout its base, inciting state-level rebellion, threatening to hold supplies hostage from those refusing to bow to such towering narcissism and self-righteousness, advocating for a decrease in testing, and enabling and encouraging the emboldened racism and bigotry the office has been propelling across the country for the past four years.

Incompetence doesn’t really seem to even fully capture what’s happening anymore.

But, behind such nationwide reluctance and those trickling moves to slow the spread of something we still don’t fully understand, I also noticed a great demonstration of something that would have had the Buddha smirking and pointing that mudra at each and every one of us while saying, “See, look what happens.”

Attachment is a powerful variable throughout life. It’s responsible for our troubling state of dukkha, Buddhist teachings emphasize, and it’s incredibly difficult to resolve – for all the multitudinous reasons that make us human. Dukkha is often simply translated as “suffering,” which is always a rather limited translation of something so interrelated to the conditions of reality, entangled with both impermanence (anicca) and lack of self or substance (anattā) – both of which are at the center of the clinging (upādāna) and craving (taṇhā) we’re perpetually trying to satisfy. This is why some translators attempt to better illustrate what is meant by further qualifying dukkha with those two concepts (impermanence and insubstantiality), along with “unsatisfactoriness” and “uneasiness.”

Life is filled with all sorts of conditions related to dukkha: pain in the most ordinary sense (physical or mental sickness or injury, being around unpleasant people or being in unpleasant situations, not having desires fulfilled, being distraught, etc.), the fading of a pleasant state or feeling (since nothing is permanent if everything is in constant flux), or the anxiety and distress associated with mental longings for certain situations or things – like, for instance, a world that didn’t see the arrival of a novel coronavirus near the end of 2019.

In Buddhist teachings, taṇhā and upādāna are typically singled out as the culprits for dukkha, with the former pertaining to those desires and thirsts that won’t actually make us happy in the greater scheme of things, and the latter being both the result and the cause, deeply connected to our misunderstandings surrounding substance, existence, and permanence. One of my favorite texts engaging these concepts and their relation to dukkha is the Ādittapariyāya Sutta, or “Fire Sermon.”

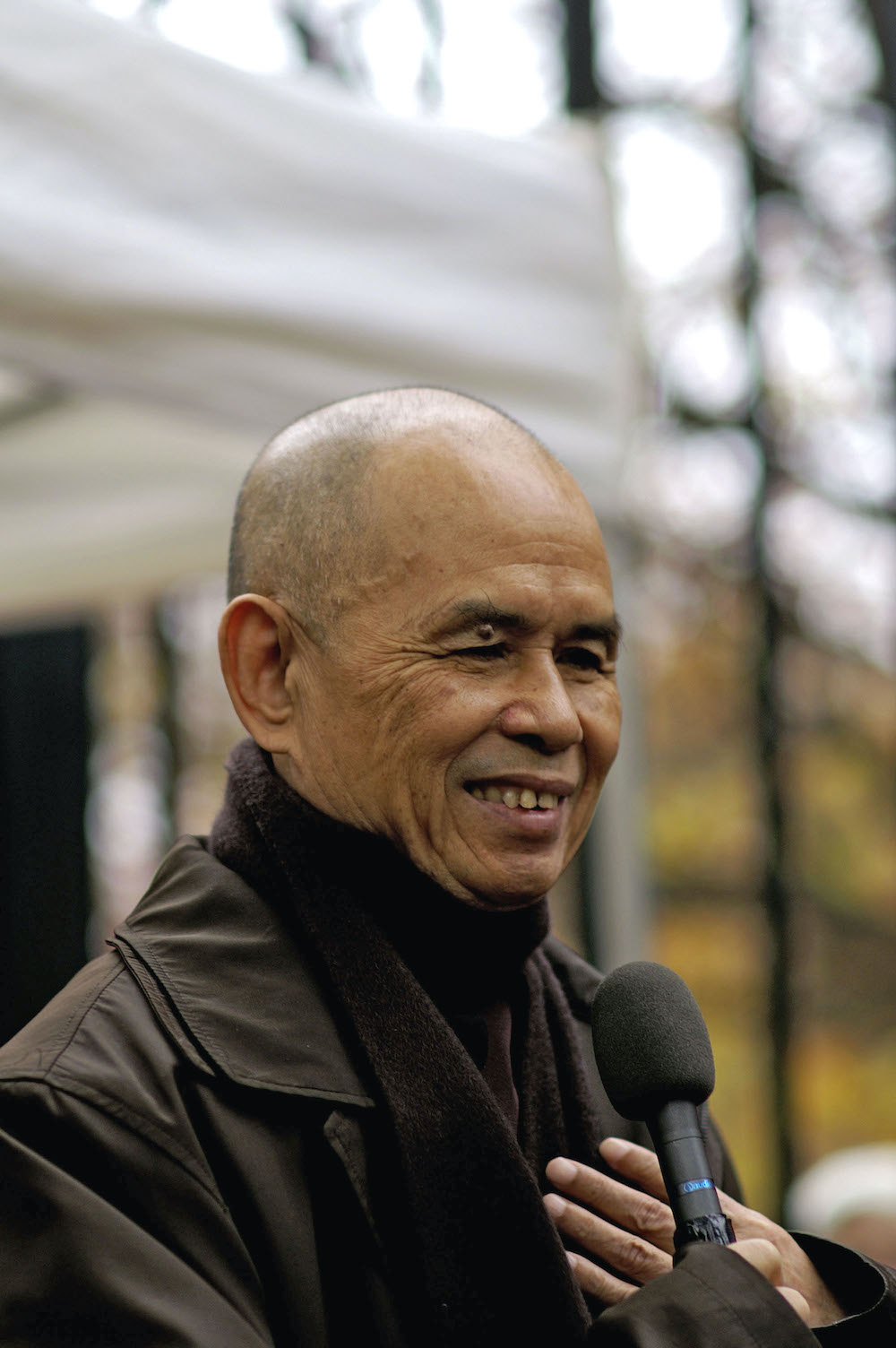

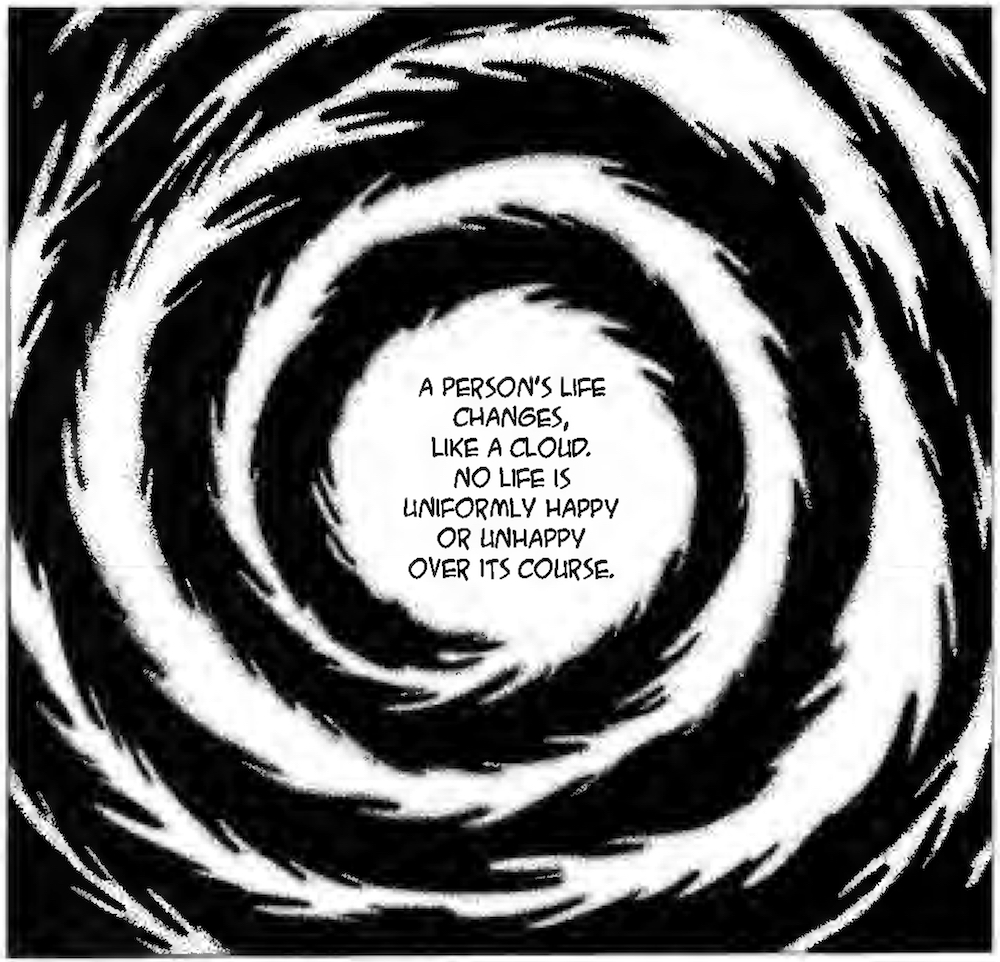

Here, the Buddha likens our thirsts to a sort of burning, analogically linking them to fire spreading from one thing to the next on an insatiable and destructive path. The point, taking into account how interconnected taṇhā is to anicca and anattā, is that such thirsts, cravings, longings, and desires can never be sated since our lives typically proceed in defiance of those latter two concepts. In other words, we regularly long for pleasurable states or conditions (including ones from our pasts) as if they were permanent, static, and not subject to change. This leads to the development of attachments towards such states, feelings, people, objects, and so on, fueling those hungry flames rather than blowing them out (nibbāna).

I’ve previously written about the implicit depiction of taṇhā and upādāna in certain television series (see this article about AMC’s The Walking Dead, a brief write-up about FX’s American Horror Story: Coven, and a more robust treatment of the latter as a book chapter), but my current doctoral work has led me to a great explicit engagement of them: Osamu Tezuka’s fantastic manga series Buddha (1972-1983).

Tezuka’s multi-volume story offers readers a remixed narrative of the life and times of Siddhartha Gautama, filled with new characters (spoiler alert: Yoda and E.T. make an appearance!), alternative accounts, and a healthy dose of anachronistic humor, along with the author’s personal emphasis on those aspects of Buddhist thought that matter most to him. It’s not an official version of the Buddha’s life and teachings (we’ll save a deeper discussion about authenticity for another time), but it’s an incredibly popular account from an author who has been dubbed the “father of manga” and a Japanese Walt Disney (look up his Kimba the White Lion, by the way, which predates exactly what you’re thinking about by almost fifty years).

At the end of volume six, being pigeonholed into specifically discussing fire by the fire-worshiping sect hosting him, the Buddha delivers his Fire Sermon.

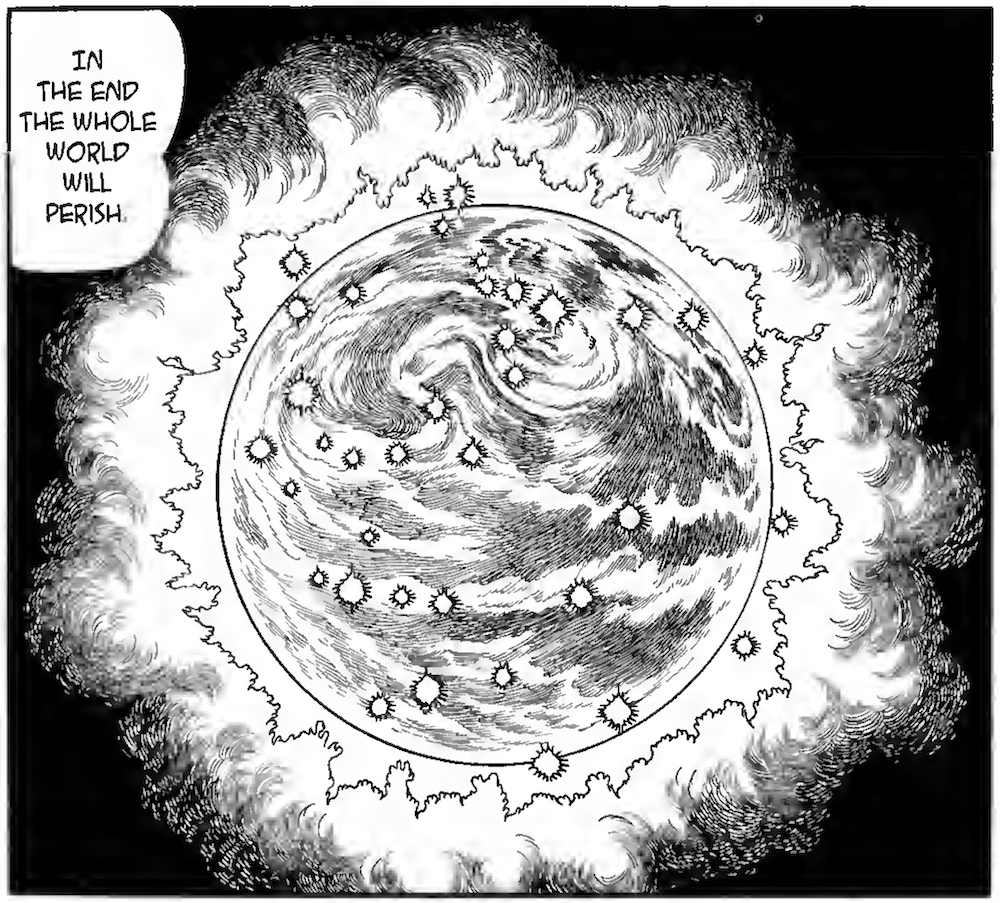

One of the stories the Buddha tells in this version of the sermon is about the young son of a water-seller. The family lives a simple life, getting by with enough food on the table, a safe and comfortable place to live, spending the days either bolstering their well or selling water in the streets of the nearby city. It’s a meager and deficient life for the son, however. The city’s lights and sounds call to him. They beckon him to feel their glow up close and sense their vibrations throughout his core. So, he runs away, finds work at a restaurant, and rises to a managerial position, striving to stomp out the competition and earn more and more money.

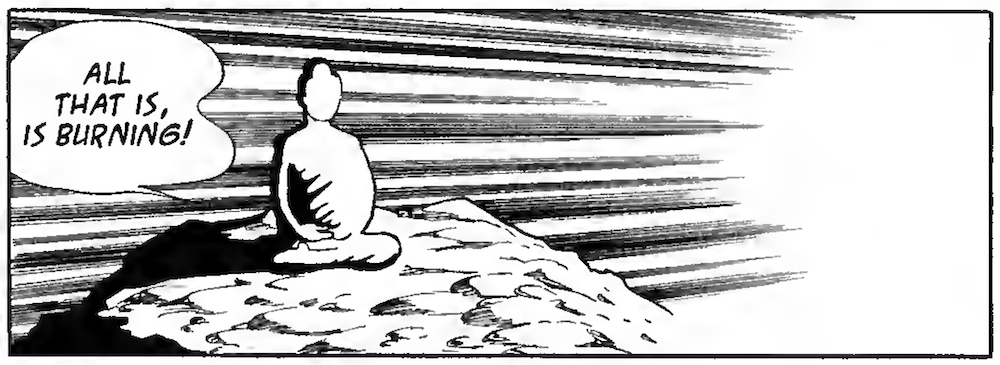

A beggar visits him one day. The son, perturbed by the decrepit embodiment of poverty, shuns him and refuses to offer any assistance. But, the beggar offers him a magic gourd: staring into it, the son can see those around him ablaze with human desire – himself included. Before the beggar leaves, he warns the son that if he doesn’t quench those flames and extinguish his attachments to money and simple pleasures, they will consume him, just as they will consume the world.

Failing to heed the advice, the son’s ambitions lead to a city-wide fire, destroying almost everything in its path…except his family’s home. With plenty of water on hand, his family is protected from the capricious flames. The son, the Buddha tells his audience, looks at his father through the gourd in the final scene and doesn’t see a single flicker of fire.

Such a story might not exactly result in a comparable conversion of fire-worshiping disciples today, but I think it’s a powerful illustration in this reworked account of how the relationship between taṇhā and upādāna fuels the unsatisfactoriness, uneasiness, and suffering throughout most of our lives.

I think it’s also a useful way to consider societal responses to SARS-CoV-2.

Change is notoriously difficult for many people. And it’s hard to accept the fact that this virus has fundamentally changed the world. It’s grown increasingly clear that there is no going back to the way things were – to “normalcy,” to pre-pandemic existence, to a society that is more nonchalant than not regarding transmittable respiratory diseases. Not entirely, at least. A vaccine might emerge one day. More efficient and successful treatments might continue to develop. But, a growing obstacle has been the lack of clarity surrounding transmission, mutation, symptoms, and long-lasting effects.

And most of us just want this to go away so we can get back to the lives we knew before all of these changes started taking place.

But, one of the most detrimental things about taṇhā and upādāna is that they cloud our notions of change and permanence. Nostalgia, comfort, and the control we feel we have in familiar situations can leave us feeling devastated when lost. Because of this, it’s understandable that such baby steps have been taken in shifting the way contemporary society operates, why re-openings have arguably taken place too quickly, why social distancing and mask-wearing have both been politicized and filled with contempt from opposing perspectives, and why it can be appealing to reassert that lost control by refusing to believe the pandemic’s severity, the effectiveness of preventative measures, or its existence entirely.

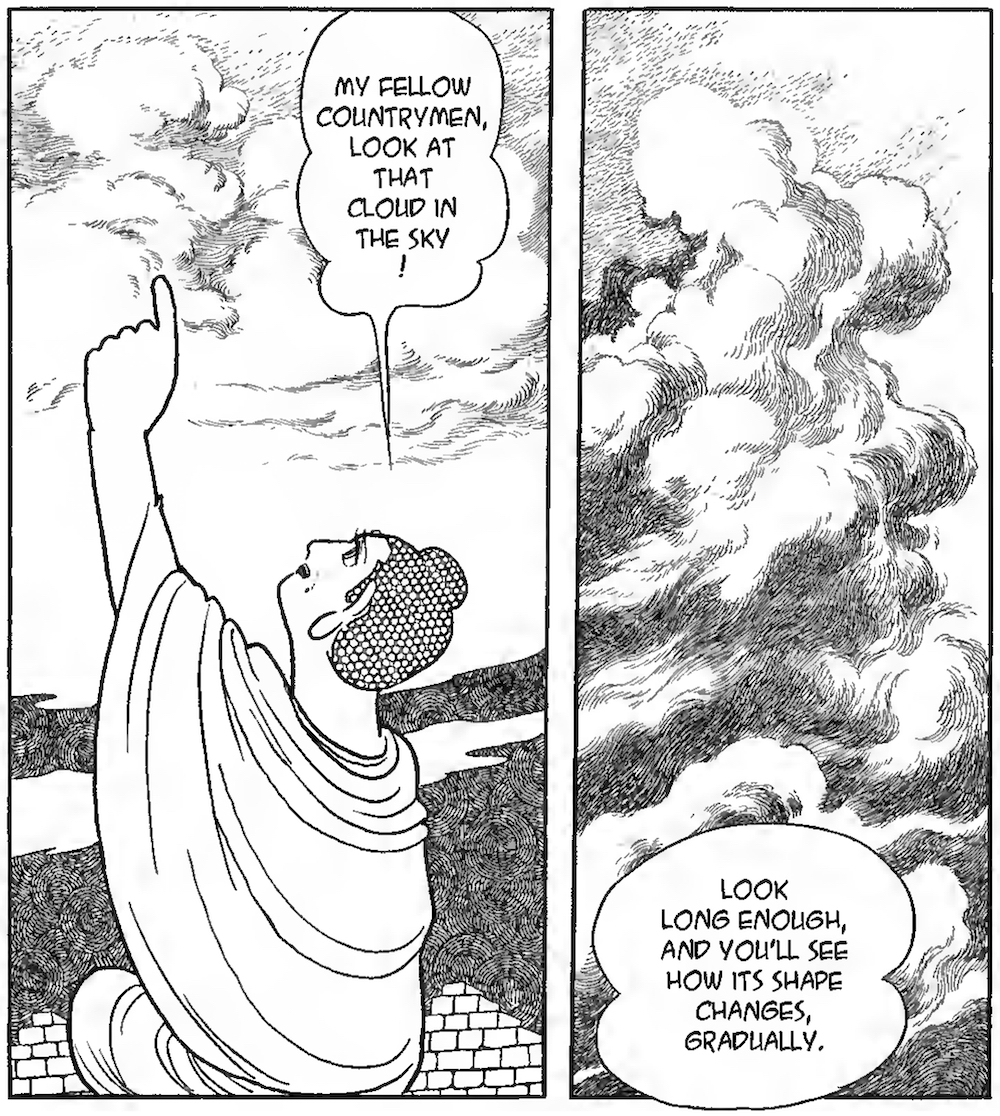

In our attachment to how things were before the pandemic’s full force was felt, we fail to realize that even the period prior was characterized by change and fluctuation, and that those moments, conditions, and feelings we hold on to from our pasts are but snippets of an ever-evolving and unstable reality.

Misunderstanding this results in stronger desires to return to former states and ways of being in the world, and the ensuing attachments will destructively consume those trapped in their blazing path: the virus’ spread will increase, more cases will lead to more deaths, and without quenching the flames that brighten the archives of the pasts from which we selectively sample, humanity and society will likely smolder well before the smoke trails emerge across the horizon.

One of the recurring themes Tezuka emphasizes throughout his story is compassion predicated on biocentricism. Indeed, mettā (loving-kindness) is an important concept in the more traditional Buddhist texts as well, but it’s clear that Tezuka understood it, rather than some of the more systematized and doctrinal complexities found in Buddhist thought, as one of the most powerful and culminating insights into the critical approach the Buddha fostered as a teacher.

Buddha opens and closes with the same story: an old man traveling on foot collapses in the desert. A fox, bear, and rabbit encounter the dying man, and each goes off to find him something to eat. The rabbit is the only one who comes back empty-handed, but he confusingly urges the man to build a fire. As the fire roars, the rabbit jumps in, sacrificing himself to feed the starving man. Tezuka revisits this story to reiterate a simple fact of life: misfortune cycles through it, trials and tribulations are an intimate part of it, and we move forward not on our own, but with the assistance of others – human and non-human animals alike – in an intricate web of connectivity, community, and self-sacrifice.

Tezuka concluded Buddha almost forty years ago. Written today, its final scenes might have depicted the Buddha wearing a mask across his nose and mouth telling those around him that doing so is not about them. It’s about everyone else. It’s about the sacrifice of those confronting the virus in hospitals and other public places every day. He’d tell them to stop holding on to the past, to stop conflating measures to alleviate a global health crisis with an infringement upon the visibility of moving lips and scrunching noses, and to be the responsible members their communities value and need.

Images from Buddha by Osamu Tezuka (Vertical, Inc., 2007); digital versions sourced from Internet Archive (volume six, volume seven, volume eight).