As the building block of civilization, sand’s conditional and combinatorial nature can help us understand concepts like impermanence and interdependence in Buddhist philosophy, especially when used in creative, meditative practices that facilitate mindful awareness.

I’ve developed quite an interest in sand over the past few months. Though I suppose it’s always been somewhat captivating for me. I’m a huge fan of sci-fi/fantasy – especially settings and stories that take place in desert landscapes. I’m not quite sure what it is about these barren locales that grabs my attention as much as montane forests. The stillness? The nothingness? The potential? Some sort of tabula rasa – for creation, for the mind? They’re uniquely meditative spaces, but I never really thought about their main component in such depth until recently.

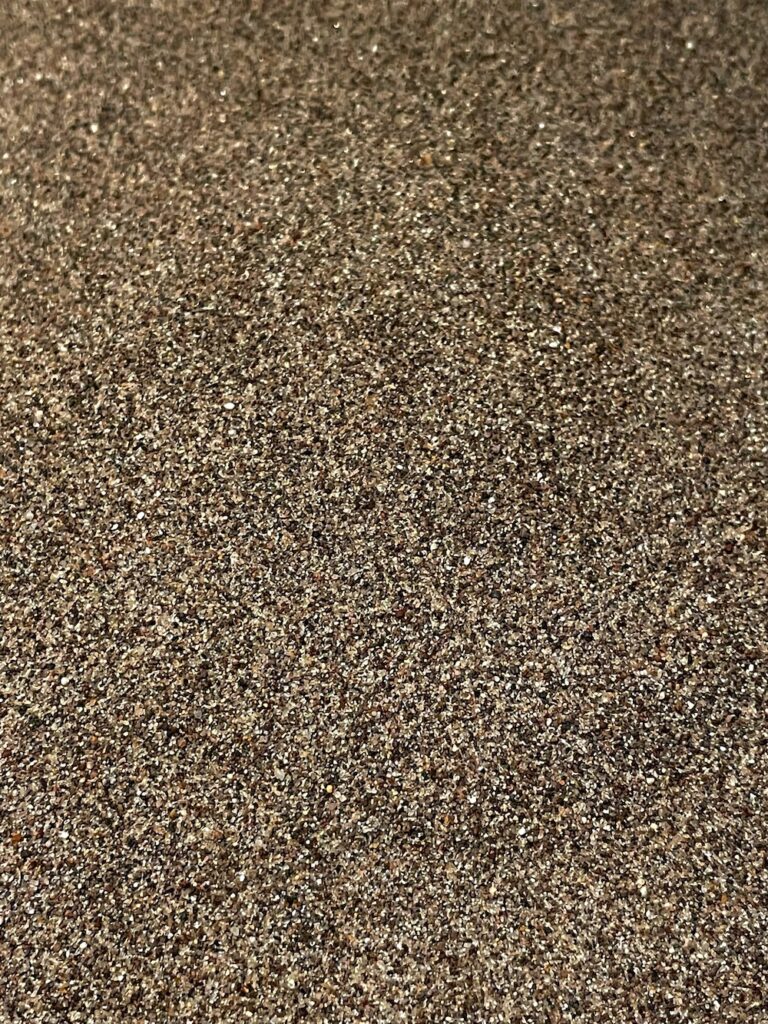

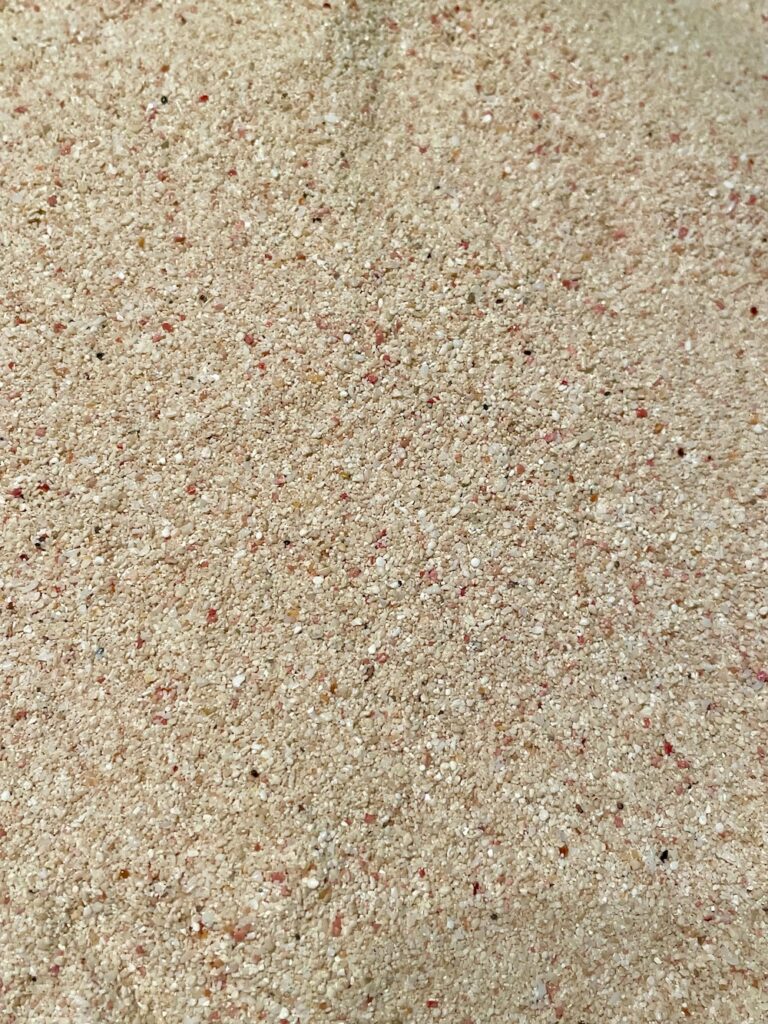

I guess such a pointed fascination started with a camping trip to the Great Sand Dunes National Park near the end of this past spring, followed by a beautiful summer vacation spent in Bermuda again for a couple weeks. I collected a little bit of sand in both places, in awe of it for its own reasons, and decided I was going to make something with the samples that captured each of those locations. Amid their similarities were noticeable differences, of course: the result of oppositional valley winds, fluctuating bodies of water, and sediment deposits from surrounding mountains characterizing the former; the white limestone sediment beautifully mixed with red foraminifera comprising the latter. And those differences were as alluring and dazzling as they were introspective and grounding.

Sand in one place is different from sand found in another. Sure. And I’ll come back to that in a moment. But it’s also everywhere. And its presence actually defines our world and interactions in it. “It is to cities what flour is to bread, what cells are to our bodies,” Vince Beiser points out in The World in a Grain (2018). It’s “the invisible but fundamental ingredient that makes up the bulk of the built environment in which most of us live,” he continues (p. 1). Building foundations, glass, paint, porcelain, water filtration, toothpaste, detergents, cosmetics, elastic, roads, computer chips, printer paper, glue…the list starts to feel endless. We encounter sand throughout most of our waking lives. It even fills our historic and contemporary myths (some of you might be watching the new adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman on Netflix, for instance). Modern life and contemporary civilization are built upon it. Quite literally. And our digital, globalized era wouldn’t be able to exist without it (it’s also non-renewable, and since only certain types can be used for such vital constructs and commodities, our growing population has brought it under as much threat today as fresh water).

But I started looking beyond this structural fact and the compositional differences that set sand apart, and realized that it can also become a really useful indicator and reminder of interconnection and conditional change. I found myself just as interested – if not more – in the symbolic features of this critical ingredient. About 70% of the sand on Earth is quartz, but every bit of it has its own unique story – its own particular origin that is intimately connected to a causal chain of events and effects, which is what sets sand from places like southern Colorado apart from coastal sand on an island in the Atlantic Ocean. There is a how and a why attached to every handful, in other words. A reason. A journey. Each handful is a moment within an ongoing process. It’s all around us, signaling an underlying and defining condition of reality. And each of those handfuls might contain grains that have already undergone millions of years of cyclic deposit, burial, and erosion – a process of transformation and change that allows us to mix it into different combinations and configurations for unique applications and purposes.

How fitting, I figured, to bring this realization into my own meditation practice and work on Buddhist philosophy and remix theory.

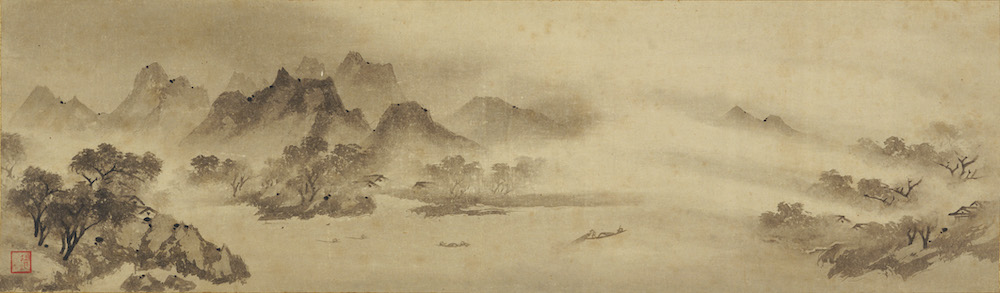

I started dabbling with sumi-e painting again this year. It’s been an interest of mine for many years, and I’ve been in love with Chinese and Japanese landscape paintings for as long as I can remember. An incredible feeling of serenity washes over me whenever I look at them. I guess that’s what finally led to me buying an instructional book and brush pen several years ago, thinking I could try to learn how to paint such beautiful works of art as well. But I just didn’t have the time to dedicate to it back then. And I’ve always been more of a textual artist than visual. Sometimes, we’re just meant to appreciate rather than replicate, I suppose.

Earlier this year, however, I bought a stack of rice paper, a few brushes, ink, and a mixed media pad, and I decided that now was the time to explore this interest again. In my own way.

Meditation has been a significant part of my life for the past year as well. The single-stroke, meditative ensō paintings associated with Zen Buddhist traditions have fascinated me for several years, so I started incorporating them into my practice after gathering up those supplies. It’s as meditative for me as sitting cross-legged on my zafu. As symbolic and soothing in attentive focus as stringing together a new strand of mala beads. It’s ink brush painting that suits me.

At their most basic level of representation, they’re simply circles. But circles have a long, symbolic place in human history. There is the celestial connection, of course: our planet is round, it spins on an axis, it orbits another spherical object, and is itself orbited by a spherical object. The expanse beyond those relationships is filled with other spherical forms and phenomena as well. The world is filled with cyclic patterns – defined by those patterns in many ways. Circular representations tend to convey a sense of wholeness, completeness, or perfection, but in Zen Buddhist traditions, they might also connote the vastness of the universe and the emptiness of the enlightened mind, wherein dualities and mistaken distinctions have been dissolved.

Ensō paintings feature prominently throughout calligraphy in such traditions, and one would think there isn’t much to their execution or much difference that could be discerned between them. But no two are ever completely alike. Ink tones and brushstrokes vary. The shape of the circles does as well – including the point where one begins and ends, and if it remains open or closed. The smallest of details add up to reflect the unique nature of these types of paintings and what they signify. “Seemingly perfect in their continuity, balance, and sense of completeness, and yet often irregular in execution,” Audrey Yoshiko Seo notes in Ensō: Zen Circles of Enlightenment (2007), “ensō are at once the most fundamentally simple and the most complex shape. They seem to leave little room for variation, and yet in the hands of Zen masters, the varieties of personal expression are endless” (p. 1). In this way, ensō paintings capture the precise moment in the minds of their creators – a thusness, a connection between mind, brush, and medium.

A moment within an ongoing process.

A brushstroke. A handful.

Both equally defining.

But the coalescence of sand, artwork, and meditation is certainly not new. Tibetan Buddhist traditions have maintained a longstanding practice of creating and subsequently destroying sand mandalas to demonstrate transience and change. While that practice also suggests some of the symbolism I’ve been sifting out here, creating sand mandalas wasn’t what came to mind for me. The first thing I thought when I looked down and started contemplating the grains between my toes was: I’m going to paint an ensō with this. It seemed perfect. The symbolism of the sand, the symbolism of the ensō. Both embodying and illustrating spontaneity, conditional change, and capturing moments – of thusness – within a casual-effective reality. An introspective aesthetic mashup, indeed.

Although, there were some details to figure out first. Painting with a brush and ink is much different than painting with sand. It took some time to figure out the best way to do it, but what worked for me was slathering a chalk paint brush in fabric glue, making the stroke on canvas, and covering it with sand while it dried. Afterwards, I shook of the excess and sprayed it with a clear adhesive to help protect the sand and keep it in place, and stamped it with a matching icon (red sand dunes for the one, a series of blue waves for the other) instead of my usual red dandelion seed tuft signature (see image above).

I also wanted to do something else with the sand – something that captured the terroir of the sampled material I sourced from these places. The raw data that could be uniquely mashed together and remixed into new, signifying creative works – something that more closely brought together the symbolism of the sand and Buddhist philosophy with remix theory. So, I designed a couple tabletop dry gardens (karesansui). Sand and stones from the Great Sand Dunes filled a round bamboo tray for the first. Sand, bits of coral, shells, and sea glass from Bermuda, with a painted ocean topped with sea salt I made with water straight from the ocean while there filled a rectangular bamboo tray for the second (see these two posts for additional images and more information on extracting the sea salt and dehydrating it).

Such dry gardens (so-called Zen gardens) haven’t exactly been a long-running interest of mine, but the more recent fascination comes from a deeper awareness I’ve developed concerning place and space (thanks to my increasing involvement in foraging and wildcrafting), coupled with some of the ideology surrounding their representation and signification. Joy Hendry notes in “Nature Tamed: Gardens as a Microcosm of Japan’s View of the World” (1997) that these types of gardens “were built to represent much more than the features of a real landscape: intended, on the one hand, to recall an ink painting of the real mountain/water landscape, after the Chinese fashion, but also to carry deeper meaning in the way the stones were arranged” (p. 94).

For me, that former association was what they became shortly after their assembly: three-dimensional landscape paintings – ink paintings that had come to life, filled with elements from the land- and seascapes to which they pointed and depicted. Ink paintings that could be interacted with in ways that actual ink paintings cannot. Ink paintings that I could create, in my own way, while I continued to marvel at the masterpieces that inspired me to pick up a brush.

“In the Zen Buddhist garden,” Hendry states, “the meditation is through elements of nature, enclosed into a work of art which represents the outside world to be sure, but the direction of attention is inward. The gardens are expected to inspire an understanding of the inner self, a clearing of the worldly distractions to be found outside” (p. 96). Of course, how the elements are arranged is also a crucial feature of these types of constructs, as well as the symbolism attached to them. Stones, one of the most common and representative components, might represent things like the heights and depths of the human spirit, or stages throughout the course of one’s life, Hendry adds. In The Art of the Japanese Garden (2019), David and Michiko Young indicate that they might also be used to signify mountains, shorelines, or waterfalls, which can then be arranged in conjunction with other items – such as small shrubs – to depict valleys and hills, or water feeding ponds or streams through the flowing patterns made in the sand (pp. 22-23, 27).

“A typical Zen idea,” the authors note, “is that the universe can be found in a grain of sand” (p. 177). I love that. Thich Nhat Hanh would regularly suggest a similar idea throughout his work (seeing a cloud in one’s cup of tea or in one’s bowl of ice cream), which I always love coming back to as well. Those types of correspondences can be really useful in helping us understand concepts like paṭiccasamuppāda (interdependence/dependent origination) and anicca (impermanence) in Buddhist philosophy, but something about sand just feels more…tangible to me.

Like an ensō painting, these granules appear to offer very little room for variation in a seemingly perfect round form. Though in reality, they too are often irregular and characterized by variety. And it is such irregularity and variety that allows these granules to be involved in the endless combinations with other source material to effectively create the world around us and condition our interaction and being in it.

Its literal foundation as the compositional building block of civilization, coupled with its microcosmic symbolism in a dry garden and its ability to capture a moment of thusness like one might through the circular stroke of an ink brush, signifies interdependence, impermanence, and mindful awareness in a truly astounding way.

And to think, such potent symbolism and signification is wrapped up in just a tiny speck somewhere between 1/16th and 2 millimeters in diameter.

Photographs taken by author (2022). “Fishing Village at Sunset” via Nezu Museum.