The sudden disruptive jolt that follows from not landing an attempted skateboard trick can offer more than an opportunity to snarl at a blameless handrail or weathered curb.

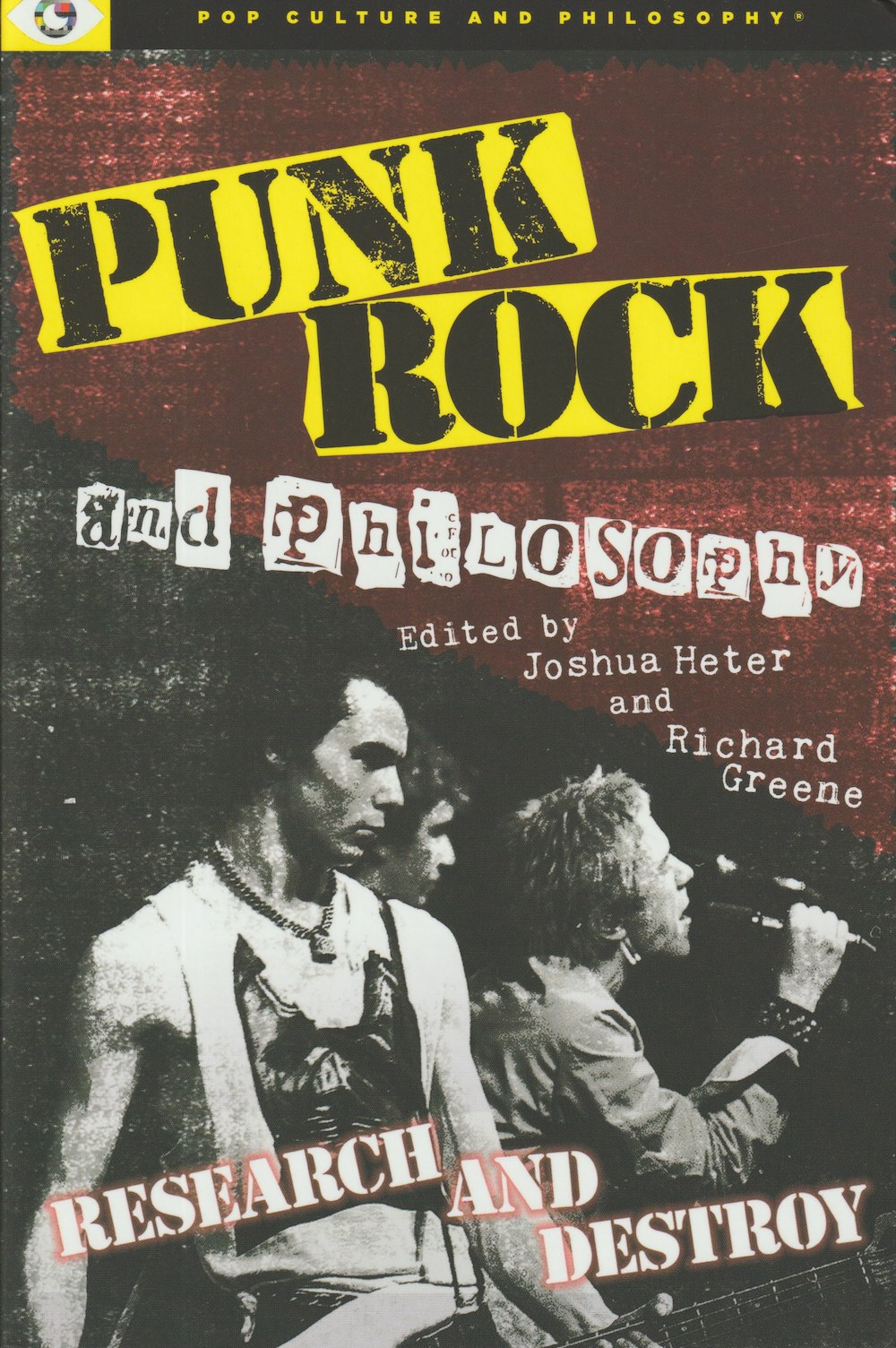

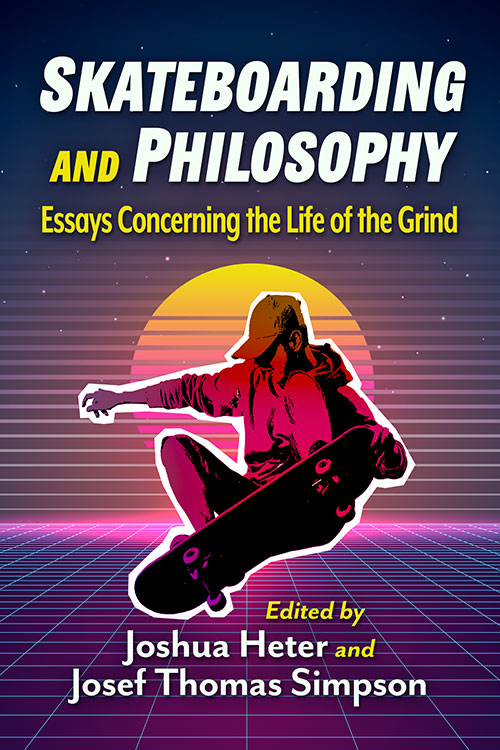

Last month, Skateboarding and Philosophy: Essays Concerning the Life of the Grind was published by McFarland & Company, featuring a mixed group of philosopher-skaters critically examining one of their favorite pastimes. I was delighted to receive an invitation from the editors to contribute a chapter as well. “The Sound of One Deck Snapping” focuses on kenshō and kōans in Zen Buddhist traditions and falling while skating. In short, I liken the jolt and impact of a missed trick to the sudden realization and insight into one’s nature sought after in Zen practice.

The introduction to the chapter appears below, followed by a brief outline of the rest of the chapter.

A cool breeze catches the hair fluttering over the bottom of your brow as you glide down the smooth asphalt. An earlier storm has left a musty aroma in the air, battling the smell of sweet, summer blooms appearing in and out of the neighboring hedges. The sun’s radiance is slow to dry what remains of the damp morning; the puddles passing through your peripheral reflect the sudden change in the day’s weather. The world seems utterly silent—the push of your foot struggling to break it—as you roll along toward a bright horizon.

Drawing similarities between various activities and meditative practice isn’t exactly uncommon. And, something like skateboarding can certainly be just as meditative as walking, if you embrace it as such. With a statement like that opening this essay, you’re probably thinking something like “Okay, I can see where this is heading: skateboarding is going to be likened to some sort of Csikszentmihalyi-like ‘flow’ experience or mindfulness practice, where you’re fully absorbed in what you’re doing to the point where it becomes capable of leading to enlightenment.” But I’m not interested in any of that, regardless of whether that’s a defensible analysis. For our purposes here, I could care less about how mindful your ride is or how meditative that pop shove-it feels to you. I’m interested in the moment when a handrail smashes into your groin because that earlier storm left it unpredictably slick later in the afternoon, when your head (helmeted, I hope) bounces off a curb because that radiant sun blinded you at just the right time, when that smooth asphalt is the only thing you smell—and taste—and when your tailbone is as suddenly cracked as the tail of your board tumbling off in the blurry distance—your agonizing howls having a much easier time breaking that silence than the foot you can no longer feel. I’m interested in the power and potential of that moment. And what that moment is capable of.

The instant leading up to a quick slide of a foot and flick of a board involves concentration, focus, and precision. But there’s nothing more humbling in the moment that follows than not landing the attempted trick. And that fall—the slip, the crash—becomes a sudden jolt and disruption that can offer more than simply an opportunity to snarl at a blameless handrail or weathered curb. Disruptive moments like this can shift our perspectives in profound ways. And it’s often through such moments when change actually happens.

Zen Buddhist traditions are known for their focus on the suddenness of awakening experiences through either “just sitting” or “silent illumination” meditative practices or the “direct pointing” of a teacher or teaching device. Often, the latter corresponds to the studying of kōans—seemingly paradoxical riddles of recorded interactions among various figures with the aim to bring about kenshō: the sudden, initial realization and insight into one’s nature or being. And, interestingly enough, many kōans recount masters literally smacking their students into spontaneous moments free of disillusionment. When one’s mind is freed from distraction and stubborn focus—when duality fades and opposition is unified—we inch closer toward satori: the much deeper resultant awakening experience. And, when a perplexing statement, story, or master’s backhand isn’t available, handrails and curbs can do just the trick.

We’ll take a look at some of those kōans below as we consider the suddenness of kenshō more closely in the context of missed tricks, snapped decks, and shattered egos. But more broadly, we’ll consider how such irritating and painful moments can similarly and abruptly knock us out of disillusionment and how they can extend to our broader lives as well: as opportunities, like any other fall, to learn more about ourselves and the world around us. Within such disruptive moments exists the possibility for awakening wherein dual modes of thinking fade in the wake of a more mindful mode of existence. And a bruised, bleeding shin can easily offer much more in this regard than just frustrated fuel for the next attempt.

Following this, I unpack kenshō, how it’s generally conceived in Zen traditions, and how the experience of falling correlates to it. I continue this discussion in the context of meditative practice and selections from the Blue Cliff Record and Gateless Barrier collections of kōans. I then revisit kenshō, encouraging readers to more deeply consider the impact of the falls and slips off their boards, indicating that these types of sudden insightful moments become the first step along a path aimed at dissolving disillusionment and dualist modes of thinking: practice—in skateboarding, meditation, or any other part of life—is deeply intertwined with persistence. And sometimes falling is exactly what we need to move forward.

If you’re interested in checking out the chapter in its entirety, along with the other essays, the book is now available!

Cover image courtesy of McFarland & Company 2025.