Disney’s new Zenimation series is more than just a themed collection of soothing vignettes. The mashup project is an extension of trends and processes characterizing both Buddhist Modernism and twenty-first-century Western mindfulness sensibilities.

Last month, during what’s become a daily Disney+ browsing ritual with my kids (a practice shared, I’m sure, with many parents during the current pandemic-induced period of social distancing and at-home isolation), I was surprised to stumble upon the description for a new, original series: “Unplug, relax and refresh your senses for a moment of mindfulness with Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Zenimation. Whether it’s baby Moana being called by the ocean, Anna and Kristoff walking through an icy forest, or Baymax and Hiro Hamada flying over San Fransokyo, these iconic scenes become an aural soundscape experience like no other.” And I’ll admit, my first thought wasn’t just how totally cool this sounded – because it did, and it is – but how perfect it would be to write about in terms of Buddhist Modernism, Western mindfulness sensibilities, and the critical dimensions of mashed-up compositions.

Zenimation debuted on May 22nd as the outgrowth of a project first presented at Disney’s 2019 D23 Expo by Disney Animation editor David Bess. The original one-scene vignettes had been stripped of the song and score accompanying them in their feature films, and viewers were left with just the sound effects often lost in the background. The ten episodes in the first season are now about five minutes long each and consist of themed, mashed-up sequences from Disney’s archives; “Water,” “Night,” and “Water Realms” are a few of my personal favorites.

“Inspired by the beautiful, iconic scenes across the worlds of Disney animated films,” the public announcement for the series reads, “the 10 episodes of animated shorts offer viewers moments of relaxation and mindfulness. Zenimation releases on Disney+ at a time when families are looking for a relaxing, soothing escape, and it offers viewers an animated soundscape experience.”

There’s certainly a lot to unpack here, but the most obvious pertains to the use of “zen” and how it is being framed. Choice in terminology captures something distinct and unique that other possible terms do not, and that choice becomes a marker for the meaning being produced in that decision. Choosing to use one term over another carries certain assumptions and goals, since different terms carry their own qualities, meanings, and conceptual baggage (“religion” is no stranger to this either, by the way). There’s a reason, in other words, why the series is titled Zenimation and not Relaximation.

Zen might signal all sorts of different things for contemporary Westerners – from ritualized daily routines, such as ōryōki practices or tea ceremonies, to meditation halls best demonstrative of “just sitting” zazen introspective techniques, or office-space desktop rock gardeners perfecting their granular patterns. In Of Remixology: Ethics and Aesthetics after Remix (2016), David J. Gunkel notes that terminological decisions are “never unimportant, incidental, or accidental,” because each of the terms “already and in advance determines the kinds of questions one is capable of asking, the kinds of evidence he or she believes will count as appropriate, and the range of solutions that are recognized as being possible” (p. 30).

In this instance, Zen is conflated with relaxation, mindfulness, escapism, and sensual experience. The animated sequence of the title itself at the start of each episode – the “a” of “animation” morphing into “zen” – signals the transformative qualities of these characteristics, too: relaxing and being mindful through the experiences these mashed-up vignettes provide can lead to a different way of being in the world.

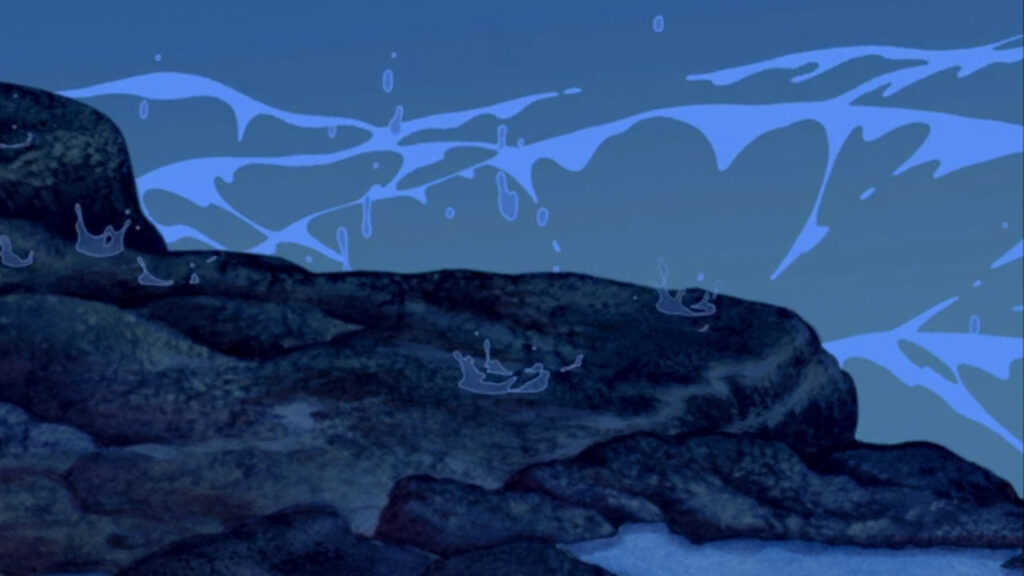

And who’s honestly not looking for a transformative reorientation right now amid such dire global circumstances that are often anything but relaxing? Zen and Disney’s visual and sound artists are here to help. It’s just a shame Disney pitches such reorientation – call it an awakening, enlightenment, liberation, or whatever – as an escape. Mindfulness meditative practices emphasize the opposite of this, really. And rather than offer an escape from the behind-the-screen lives many of us have adopted even further these days with yet additional screen-filled media, Zenimation’s mashups can help us recall the inherent beauty in the world through classic moments in the masterpieces from our childhoods and those of our own children.

The sound of leaves crinkling in the wake of intentional steps, flowers and trees blowing in a soft breeze, rolling tidal waves splashing droplets across breathtaking shores, starlit skies brought to life with a chorus of chirping onlookers, and the dazzling splendor of both cityscapes and untouched utopian wildernesses are more than just the fabricated animations of the realities we long to actually experience. They are reminders that our lives can already be experienced in such sensuous ways – if we slow down and pay attention – and that there is still beauty in a world plagued by viral outbreaks, marked by scorched and scarred landscapes, and increasingly ravaged by isolation and desolation. Such reminders come easier, of course, for those least affected by calamity to begin with, but Zenimation offers more than just a fresh, privileged, and assumptive solution to the obliviousness and unintentional orientations characterizing our relationships and interactions. It fits well within a legacy of mindful reorientations toward the world that have become increasingly transhistorical, transcontinental, and transcultural.

While Zenimation certainly offers a unique and nostalgically-stunning mashup of stellar animation and serene soundscapes with mindfulness sensibilities, merging Zen with cognitive, behavioral, and counter-cultural traditions in the West has been regularly taking place since the middle of the last century. Much of this, and the general transplanting of Buddhist thought and practice outside more traditional settings in Asian contexts, pertains to modernizing processes of detraditionalization, demythologization, and psychologization. David L. McMahan, one of the leading scholars on Buddhist Modernism, outlines these processes in greater detail in The Making of Buddhist Modernism (2008), but in brief, detraditionalization refers to the process of breaking away from institutional structures and external authority to embrace a more privatized and individualized form of practice and newer structures usually encountered as “workshops” or “retreats”; processes of demythologization recast elements in ways that make them relevant and practical for more modern worldviews – like interpreting the realms of rebirth as analogical states of mind rather than actual places; and psychologization carries demythologizing to a state of synonymity with Western psychology, wherein deities and celestial beings become archetypes, meditation becomes the most important tool for relaxation and enlightenment, and Zen becomes a state of mind.

Mindfulness meditation and understanding Zen as a state of mind have become the most common features in the migration of Buddhist thought to Western contexts – even though the accuracy of reading these now Western features back onto preceding Asian contexts remains disputed – and they have synchronized well with the curative offerings of Western therapeutic practices; see Mark Epstein’s work in this area – in particular, his famed Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective (1995).

The Buddha-as-physician analogy – providing a diagnosis, explaining the cause, indicating its remedy, and outlining a plan for treatment – has become a common way to think about the Buddha and his teachings (see the Māgaṇḍiya and Cūḷa Māluṅkyovāda Suttas for examples demonstrating this association). In many ways, sought after Zen-like states of mind clearly demonstrate the curative features of a Buddhist “treatment plan,” and the non-institutional subjective framing often accompanying it has become even more common amid those psychologizing and demythologizing processes, further detraditionalizing Buddhist thought and practice in non-therapeutic settings for non-Buddhist goals without requiring an explicit commitment to Buddhist values.

Western meditative practices associated with these processes, however, become interpretations of Buddhist meditation “informed by a cluster of emancipatory aspirations deeply rooted in western modernity,” McMahan states, “including not only Romanticism-inflected subjectivism and psychoanalysis but also the ever-present, tacit assumptions of liberal social and political theory and its emphasis on the freedom of the individual from external constraints” (p. 196). The Buddhist treatment plan becomes, then, an alluring way to address one’s symptoms – whether physiologically related to the contraction of something like a global viral strain, or to the mental hardships induced or accelerated by its presence in the world. And Zenimation is positioned as a beautiful prescription for helping one do so.

It’s also a clear example of Disney officially practicing something it generally tries to prevent among fan and DIY cultures.

There’s some heavy irony underlying Disney’s role in a recombinatory creative venture related to both its historic practice of repurposing free- or fair-to-use material in its creations, and its legacy of making sure others cannot subsequently do the same thing with those productions – a stance Disney continuously reasserts in its lobbying for copyright extensions whenever Mickey Mouse starts edging closer to entering the public domain. Contemporary mashup practices regularly engage issues surrounding copyright via the transparency of content being repurposed and the cues that direct audiences back to originating source material. And even if mashups aren’t explicitly critical, they often function critically in their engagement of the parameters surrounding contemporary modes of production and ownership, signaling the subversive impulse with which many remix artists approach traditional notions of authorship and originality in their work (see my analysis of Westerosi zombies in Game of Thrones for more on the critical role of regression and reflexivity in remix).

Today, it’s not beyond the reach of any proficient audio-visual editor to do something similar to Zenimation on their own, given the right tools and practical skill set. And yet, rarely can they get away with making such productions available to public audiences without repercussions. Maintaining control over the ways in which its material can be reworked seems to run counter to the creative sensibilities characterizing productive practices in a culture predicated on recyclability – especially when Disney dictates who can do what with its content – but the legal parameters that have developed alongside Enlightenment-era notions of ownership and property render this an unfortunate, and often exploitative, part of society.

Zenimation also isn’t the only place where viewers can find Disney remixing its own material. Several films, shorts, and series sample or parody prior content, but the most obvious demonstration of this can be found throughout the animated Aladdin franchise with one of my favorite Disney characters: Genie. As a remix artist extraordinaire, he’s constantly participating in some form of cultural citation, either parodically drawing on celebrity figures, playing with all sorts of popular cultural references, repurposing tropes and moments, or even remixing other Disney-produced content. His “Steamboat Genie” in Aladdin and the King of Thieves (1996) is one of the best and most potent examples of this. Here, Disney can be seen remixing Disney via the paramount, copyright regime-starting short that introduced Mickey Mouse to a burgeoning twentieth-century creative culture: Steamboat Willie (1928), which was itself a product of recent innovation in sound synchronization (specifically found in The Jazz Singer, released the previous year), the Arthur Collins song “Steamboat Bill” (1911), and Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr. (released about six months prior to Disney’s famed short).

But beyond the critical dimensions of mashed-up productions here is a beautiful collection of soothing vignettes that extends those trends characterizing modern mindfulness sensibilities, mashing together the mastery of Disney’s creative forces and the unique signification of Zen in the Western world.

One of my favorite things about Zenimation is that it complements the sights and sounds found within beautiful landscapes and urban settings with an emphasis on the serenity of the everyday mundane: the clack of wet feet pattering across a tile floor, jewelry melodically clanking together, engines humming across the sky, the kicking of a ball, the gulp of a thirst-quenching drink, cars driving by, a match being lit, or even the slow-forming smile suspensefully spreading across a helpful sloth’s face. Zenimation pushes viewers to also look past the obvious candidates for mindful appreciation – a rising sun, calm waters, lush greenery – in a true reorientation instead of just suggesting a mere turn in another direction.

Commenting on his inspiration for the project, Bess cites a scene in Frozen (2013), when Anna and Kristoff are walking through an icy forest: “The characters are enjoying the view, looking around. Kristoff takes his hand and brushes the icicles and walks by. It’s beautiful.”

Indeed, it truly is. And moments like this don’t offer an escape from the world. They offer an embrace. Perhaps that is what the “zen” in Zenimation signals most.

Images from Zenimation via Walt Disney Animation Studies 2020. Image from Aladdin and the King of Thieves via Walt Disney Television Animation 1996.