Dwelling between the old and the new can provide a contemplative space where we might slow down and become more attuned to our senses and surroundings as we prepare for what’s next.

Star Wars: Galaxy of Sounds recently premiered on Disney+, adding to an ever-increasing lineup of Star Wars media. Like other fans, I certainly haven’t been disappointed with this trend. Those of you who have been watching Zenimation (recall my post about the series last year) probably noticed some immediate similarities in the official description of this series as well: “‘Star Wars Galaxy of Sounds’ explores the ambience of a galaxy far, far away through themes such as wonder, excitement, oddities, and more. Be immersed in the hum of Coruscant at golden hour, listen to the light side of the Force as Rey connects to past Jedi, and observe booming lightsaber duels. Experience the nostalgic sounds of Star Wars from across the franchise.” Indeed, the new series engages with such sights and sounds in a similar, meditative way, but I’d say it’s more so an experience revolving around excitingly mashed-up sequences from our favorite films and live-action series (as of right now, just The Mandalorian) than it is about unplugging for a so-called moment of mindfulness with Disney’s animated feature films. Nevertheless, the first set of episodes was a fun treat – for any Star Wars junkie, I’m sure – and the series, which is still uniquely meditative, debuted at a time when I’ve been trying to slow down and become more attuned again to my own senses and surroundings.

I finished my PhD this past June. Most probably assume there’s an intense and abrupt feeling of finality accompanying such a moment. That hasn’t really been my experience, though. People – friends, family, colleagues and customers at the brewery where I’ve been working – have been asking me what’s next since they first started facetiously asking if they now have to call me “doctor.” I don’t know, I’m still sort of decompressing. That’s been my answer. It’s true, for the most part. But, I also find myself feeling like I’m in this in-between state, having completed something major that occupied my life for a long time, yet feeling like I’m still perpetually stumbling along the edge of a forest with no discernible clearing in sight. Though I guess major events in life are also often accompanied by deep introspection, which can be both illuminating and scary.

There’s a scene in Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love (2006) when she’s describing the discovery of her word in India that hit me like a Slave I seismic charge when I recently came across it again.

Antevasin.

For those of you unfamiliar with the book (or film), this is a scene (Chapter 69 in the book) recalling a conversation she had with friends in Rome earlier on her trip revolving around particular words that represent – somewhat metonymically – something else, such as a city – Rome’s word is apparently “sex” – or person, which is what Gilbert has been waiting to figure out for herself up until this point. She found it while reading an old book on yoga at the ashram where she was staying, in a description about ancient spiritual seekers. As she notes, it means, “one who lives at the border”:

In ancient times this was a literal description. It indicated a person who had left the bustling center of worldly life to go live at the edge of the forest where the spiritual masters dwelled. The antevasin was not one of the villagers anymore – not a householder with a conventional life. But neither was he yet a transcendent – not one of those sages who live deep in the unexplored woods, fully realized. The antevasin was an in-betweener. He was a border-dweller. He lived in sight of both worlds, but he looked toward the unknown. And he was a scholar.

I’ve always really loved the meaning behind antevasin since I first heard it, well before more recently reading this specific passage. But, coming back to it again now, at this particular moment in my life…it carries a different sort of weight.

An in-betweener. A border-dweller. That seemed about right. A scholar? I guess I need to start getting over my persistent imposter syndrome and start embracing that label without feeling so pretentious about it?

But anyway, I really connected with this qualification – both the first time I heard it, and again now – and I still think about it often, especially in the more figurative sense Gilbert outlines in the second part of her description:

In the modern age, of course, that image of an unexplored forest would have to be figurative, and the border would have to be figurative, too. But you can still live there. You can still live on that shimmering line between your old thinking and your new understanding, always in a state of learning. In the figurative sense, this is a border that is always moving – as you advance forward in your studies and realizations, that mysterious forest of the unknown always stays a few feet ahead of you, so you have to travel light in order to keep following it. You have to stay mobile, movable, supple. Slippery, even.

That shimmering line between the old and the new. Always learning. Always following the edge of that mysterious forest of the unknown. Yeah. Definitely. And here’s when Gilbert really got me hooked on this: when she mentions (in the book) the poem one of her friends wrote for her when he left the ashram, referring to her in it as being “betwixt and between,” navigating varying roles and ways of engaging with and being in the world, slipping around in an in-between state…like a fish. A “slippery antevasin – betwixt and between – a student on the ever-shifting border near the wonderful, scary forest of the new,” Gilbert concludes about herself.

This wasn’t the first time I came across the phrase “betwixt and between” either. In fact, anyone who has formally studied religion or anthropology most certainly has at some point. It was popularized in Victor Turner’s anthropological work on rites of passage and the symbols and rituals that characterize them. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (1969) famously outlined that period during which one moves from one state into another. Turner, repurposing ethnographer Arnold van Gennep’s work before him, framed this as a three-part process involving 1) separation, 2) liminality, and 3) aggregation. Separation, as the term suggests, is characterized by a sort of structural disassociation – social, cultural, whatever. And that second stage, the liminal period, marks an in-between, anti-structured state prior to one’s transition into what follows (i.e., aggregation). The idea here is that one undergoes some sort of transformation during this liminal, in-between state, and the model can be (and has regularly been) exported in understandings of various transitional processes or periods in one’s individual or collective life (I’ve actually written about it in previous theses as well, in terms of experiences associated with popular music and regarding the intentional space found in alternative communal living).

This is how Turner phrased it back then: “Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial. As such, their ambiguous and indeterminate attributes are expressed by a rich variety of symbols in the many societies that ritualize social and cultural transitions” (p. 95). It’s a phase often likened to death or being in the womb, invisibility or a solar or lunar eclipse, and darkness or wilderness – the latter being much like we might find at the edge of…a mysterious forest.

I don’t think I ever really thought of myself as being betwixt and between right now in the way that Turner described, but Gilbert’s figurative description of the antevasin, coupled with her friend’s poetic rendering, of course, does mash the two together in a way that strikes me as comparable. And certainly relatable.

I started something major in my life several years ago, completed it, and yet still feel like I’m in this sort of in-between state – that I’ve simply advanced along with that border and am still watching it closely. And don’t get me wrong, this isn’t exactly an unsettling feeling. Not all of the time, at least. It’s been a much more contemplative space recently as well, especially as other areas of my life coalesce right now and are being more deeply considered too. Thresholds tend to be inherently contemplative spaces, I suppose. And I guess that’s usually a good thing.

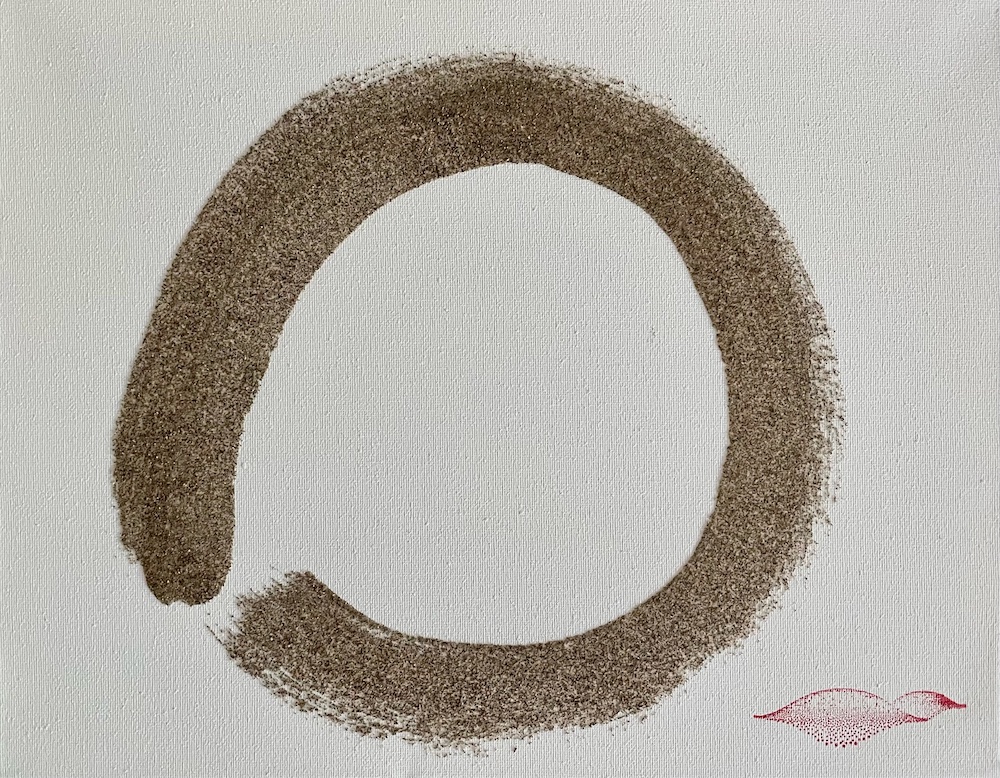

I’ve been taking meditation much more seriously now. Every morning, before dawn, I sit with my hands in my lap and stare out my window towards a horizon filled with peaks beginning to reflect the early beams of first light. Their grayness in those moments reminds me that there are shades to our darkness; there’s something waiting to poke through, if time and space is given for it to manifest. Sometimes, I join a guided zazen session with the Zen Center of Denver via Zoom. I have reminders that chime on my phone for shorter mindfulness moments throughout the day, too. I recently stitched and stuffed a zafu for myself as well (a traditional Zen meditation cushion), and have started making wrist malas for myself and others as a regular hobby. I’ve noticed that meditation works on multiple levels in that regard: the creation of these items is itself meditative for me, and they are, of course, used during meditation.

But, I guess reflecting on this reminds me that we’re all embarking on our own, particular journeys. We have been, ever since we first started to more intentionally perceive ourselves and our surroundings. And they don’t always end when something momentous or drastic has occurred or been accomplished – and those particular instances aren’t even necessarily the parts of our lives that are in the midst of culminating or being sorted out. What’s being pinpointed as the accomplishment we should feel accomplished about, for example, might not actually be the main thing characterizing such in-between space more than something else we’re trying to figure out.

Gilbert’s journey during the time she reflected on in Eat, Pray, Love was largely characterized by finding her word, in that it revealed something important to her about herself. And I like that notion: being someone in search of a word – especially given the way classification, labeling, and representation are generally conceived to operate in conjunction with language. But, I don’t think I’m interested in just one word (though I do really love antevasin!). Maybe my journey is more so about discovering what certain words like that mean to me rather than seeking them out in order to seemingly define me. However our journeys in life proceed, the important thing is having the space to reflect on what is being felt and experienced so we can either emerge from that liminal space or continue to push its boundaries forward.

There’s another word Gilbert revisits frequently in Eat, Pray, Love. It’s one of her favorite words in Italian: attraversiamo. It means, “let’s cross over.” As in, to the other side of the street. At first, she indicates that she really just loves the way this word sounds, but as it begins to reappear, you start to sense the symbolism of crossing over she’s alluding to as well: from one point in life to another – across a liminal boundary to the other side, to the new that terrifyingly and wonderfully awaits. And although she doesn’t explicitly state how complementary and related the meanings of antevasin and attraversiamo are for her journey, I think it’s a journey entirely characterized by the interplay between them, and one that many of us can relate to as well: standing at the cusp of an in-between, border space, following it as we always advance towards the new, and finding the courage to make the decision to cross over when we need to. The words are connected and clasped together like two hands that can’t let go. They’re simply impossible to separate.

One of my favorite writers, Albert Camus, wrote a short piece in the 1930s titled, “L’Envers et L’Endroit,” which, coincidentally, gets translated sometimes as “Betwixt and Between” (or, “The Wrong Side and the Right Side”). But, that border is framed much differently for him. It’s not one between the old and the new. It’s between love and despair. And for Camus, the two form a similar, ever-shifting balance: “There is no love of life without despair of life,” he writes. I’ve known no other writer to so passionately and poetically frame both his disgust and admiration for his surroundings in the face of an absurd world than Camus. And it’s a framing that equally beckons us to reflect upon our feelings and emotions as we slip around between and cross through the states that structure our lives.

Those borders and in-between states might be found amid the old and the new, love and despair, joy and pain, or even anger and sadness, but they are often each characterized by their own, scary forests nonetheless. Sometimes sitting still and monitoring our breath is enough to help navigate that space. Sometimes seeing the world in all its horrifying and magnificent splendor is, too. But, there are also those times when cosmic montages filled with proton canons and dueling laser blades provide the perfect means for slowing down to feel the energy and force around us as we prepare for what’s next.

Standing at our borders and making our crossings. That’s life. And that can certainly be feared. It often is. It often should be. But, it’s also how we turn that vision of the new into the new. How we grow. How we move forward. How that despair becomes love. And yeah, that’s scary. It’s terrifying, really. But it can also be really beautiful. Two hands, clasped together. And that terror and beauty…that’s what largely defines life itself.

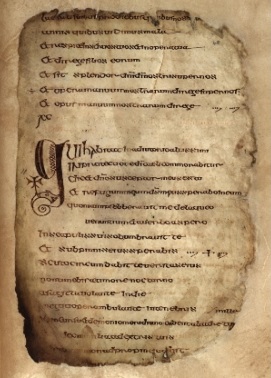

Photograph taken by author in Estes Park, Colorado (2021).