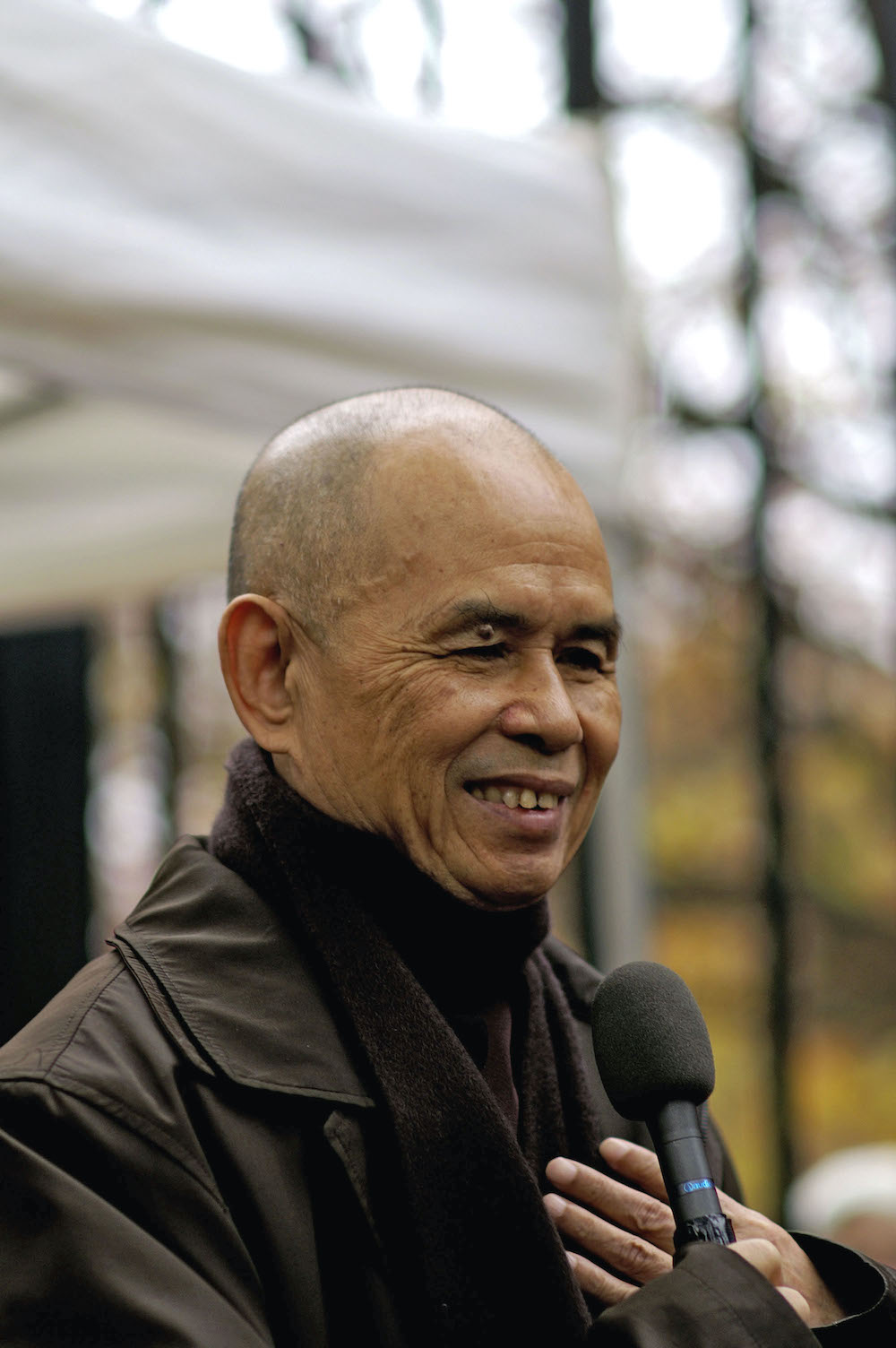

Thich Nhat Hanh’s life and teachings remind us of the importance of being present in our lives and that everything is always constantly changing rather than being created or destroyed.

One of the first books I purchased on Buddhism was Thich Nhat Hanh’s The Miracle of Mindfulness, a text he initially wrote in the mid-70s that has since been reprinted several times. I often tell people – especially those coming to Buddhist thought and practice for the first time – that this book forever and fundamentally changed the way I view the world and my place in it. The present moment is the only moment in which we’re actually living. Dwelling in the past, anticipating the future…those preoccupations simply prevent us from living. If you’re looking for a quick and to-the-point summary of the book, that’s it.

His recent death didn’t exactly come as a surprise to me (he was 95 years old and suffered a severe brain hemorrhage in 2014), but it was still upsetting to read about. Thay (or, “teacher,” as his followers often called him) spent most of his life dedicated to peace and bringing the Buddhist practice of mindfulness to those around him. He was an incredibly prolific writer whose central message concerned recognizing, and being present with, our thoughts and experiences. He was my gateway, so to speak, into Buddhism. His teachings opened me up to several other Buddhist writers and academics, leading to writing of my own on Buddhism and a doctoral dissertation centered around examples and case studies from various Buddhist traditions. It also didn’t really surprise me, then, that reading about his death stirred quite a bit of reflection and awareness of a personal and professional past shaped by his work.

My favorite anecdote of his appears in the first chapter of The Miracle of Mindfulness: wash the dishes to wash the dishes, not to simply have clean dishes. It’s about being here. And now. In the present moment. The only moment that really matters. The only moment in which we are actually alive.

Washing dishes, of course, is just an example. You could replace it with just about anything. But the idea is simple: when you’re washing the dishes, focus on washing the dishes. Don’t think about what you are going to do after you hurriedly wash them. You’re not in the moment, then. You’re dreaming of the future – a time that does not yet exist, and odds are, won’t actually exist in the precise way you’re envisioning it while not living in that present moment. Don’t think about the meal you had prior to dirtying the plates and bowls underneath your soapy fingertips either. That time has passed; acknowledge it and what it means to you, and let it go. In short, washing the dishes is a meditative act of being there with those dishes in that moment, focused on what you’re doing right then and nothing else. So again, swap out washing the dishes with whatever suits you, but the principle remains the same: here and now. Be there. Be present. And find peace.

My favorite line, however, appears in his Peace is Every Step (1991), and I think it’s a fitting complement to his emphasis on washing the dishes in order to wash the dishes: “Walk as if you are kissing the Earth with your feet” (p. 28). It occurs amid a discussion of walking meditation, and how our walking is typically characterized by an obliviousness and anxiety-laden preoccupation with something else that causes us to miss the beauty that surrounds us – beauty that we are often ironically and desperately searching for in every place but right in front of us.

This is something we all struggle with, in varying capacities. But something that has helped ground me in the present moment when I’m walking around outside is a more recent practice of foraging for wild edibles and medicinal plants. What started as an unexpected survivalist hobby at the onset of SARS-CoV-2 has turned into a way of life characterized by the appreciation of what often goes unappreciated, if not outright rejected, but is so incredibly valuable and beneficial, wild and beautiful. And as I reflect on it, I realize how wonderful of a metaphor it becomes for all else in life that is full of wonder and awe that we simply dismiss or look past because we’re either moving too fast, filled with thoughts outside of the present moment, or clouded by ignorance. And it fills that practice of foraging and appreciation with much more meaning and inspiration for me as a result.

Such passages and stories from Thay’s many books have flooded my mind for the past few days, but one of his books in particular – and the passages contained therein – has continued to linger more than others: No Death, No Fear (2002). In this book, he more explicitly outlines the erroneous nature of our typical notions concerning birth and death, which largely rests on a reminder of what the “self” is in Buddhist thought.

In response to Upaniṣadic philosophy, the Buddha taught that there is no permanent, essential self (ātman/attā). Let’s call that Self with a capital “S” (akin to something like a “soul”). What we perceive as Self is simply a complex conglomeration – a composite of five parts according to Buddhist philosophy: physical form, sensation, perception, mental formation, and consciousness. Those components come together based on a conditional, impermanent, interconnected, and interdependent reality characterized by cause and effect. This is so fundamental that even the distinction between cause and effect begins to blur upon closer analysis.

But the point here is that the typical understanding of a life span and personal existence runs counter to this: birth and death are just notions. They aren’t necessarily false notions, per se, as long as they are understood as categorical in their normative sense and not as essential markers of creation out of nothing and destruction into nothing. In other words, if there is no Self (anātman/anattā), then nothing uniquely separate is ever born, just as it can not simply cease to exist upon death. Instead, life and its appearances of birth and death are wrapped up in what Thay calls “a constant process of manifesting” (p. 13). A constant process of becoming. Of interdependent transformation. Of conditional change. He often referred to birthdays as “continuation days” because of this. I’ve always loved that.

In several of his books, you’ll find a common analogy demonstrating interconnection and interdependence involving a wooden table – a wooden table that wouldn’t be a table without the pieces of prepared wood and screws holding it together. But just breaking it down to those main ingredients – prepared wood and screws – isn’t that simple either: someone (a carpenter) had to craft that table, and those parts don’t just appear out of nowhere. The wood is the result of a tree – a tree that needs sunlight, rainwater, and soil filled with the right nutrients in order to grow. Without the raw iron ore, there wouldn’t be any screws. Take away the water, and the tree wouldn’t be there. Similarly, remove one of the carpenter’s parents from the equation (or a great-great-great-grandparent), for instance, and the table wouldn’t exist.

In No Death, No Fear, Thay uses the “birth” of a cloud to illustrate the same thing, but even further removed in order to see how dependent rain itself is on certain conditions and components:

Before being born it was the water on the ocean’s surface. Or it was in the river and then it became vapor. It was also the sun because the sun makes the vapor. The wind is there too, helping the water to become a cloud. The cloud does not come from nothing; there has been only a change in form. It is not a birth of something out of nothing. Sooner or later the cloud will change into rain or snow or ice. If you look deeply into the rain, you can see the cloud. The cloud is not lost; it is transformed into rain, and the rain is transformed into grass and the grass into cows and then to milk and then into the ice cream you eat (p. 25).

The point is that everything is connected, dependent, and constantly changing. Human lives and relationships aren’t any different. Something cannot come from nothing, and no one can ever become someone. There is only continuation. Transformation. Manifestation.

This framing aligns really well with some of the main principles guiding remix theory too, which is one of the reasons why Buddhist case studies and examples formed the bulk of my dissertation project. Thay indicates that we can understand everything surrounding us “as a manifestation that has come from somewhere and will go nowhere” (p. 32). Creation and destruction aren’t opposites. They probably aren’t even the best terms to be using. Manifestation, Thay reasons, better signals the changes in form that other terms such as these (along with birth and death) load with misconceived (and often metaphysical) notions.

A remix is predicated upon the sampling of already existing source material and the reassemblage of that material into something different. And that is precisely what we see taking place here – whether we’re talking about the components of a wooden table, the elements contained in a cloud, or the composition of a living being. Phenomena continue in their manifestations and transformations in perpetuity. And they do so through the combinatory processes that structure their differences, developments, and changes.

Buddhist philosophy discerns the inherent flux of reality. Everything is impermanent. Everything is constantly changing as a result of interdependent conditional chains of cause and effect. There is no creation ex nihilo – no creation out of nothing. There is no annihilation. There is only change involving that which already exists – ex materia – and will continue to exist amid continued transformation and manifestation.

Yeah, including Thich Nhat Hanh.

Thay always emphasized how far this interconnected reality stretches: we are the perpetual products of our relational and natural interactions, and we are continuously and constantly shaped by them. We are our parents, remixed. We are the natural world, mashed up. And our creative dispositions will never come from nothing either. Remix doesn’t necessarily signal constant change, but it does offer us another way to think about continuation and the inherent process of sampling for in what we might call creation, and from in what we might call destruction. There’s some truth, then, to those pleasant, pithy remarks about people never really leaving us. And while we might be saddened by such tangible losses in our lives, we can also use those moments as opportunities to recognize the very nature of existence.

Thich Nhat Hanh certainly impacted many people throughout his life, so hopefully his followers can delight in recognizing that his continuation is through them as well. But his central message was never just about how to be a good Buddhist. The context for his teachings aside, it was more generally about presence and appreciation. The two are so intertwined that it’s impossible to be appreciative if you aren’t present; it’s impossible to be present in a given moment if you aren’t appreciative of it. And that appreciation might not only be for what is there; it might pertain to what is not there as well. Whether you’re drinking a cup of coffee, reading a book, cleaning up a mess, or kissing the Earth with your feet through a field that’s exploding with the most spectacular sights and sounds…be present with that one thing. Even if it’s unpleasant or painful, upsetting or jarring. Be still and appreciate it for what it is. Because if you go too fast, if you try to juggle too much or too many thoughts or practices at once, you’ll only get to enjoy and be with – or learn from – just a sliver of each. And it’s in that whole present moment of stillness and appreciation where we grow and find peace.

Photograph of Thich Nhat Hanh taken by Duc Truong (2006) / CC BY-SA. Photograph of purslane taken by author (2021).