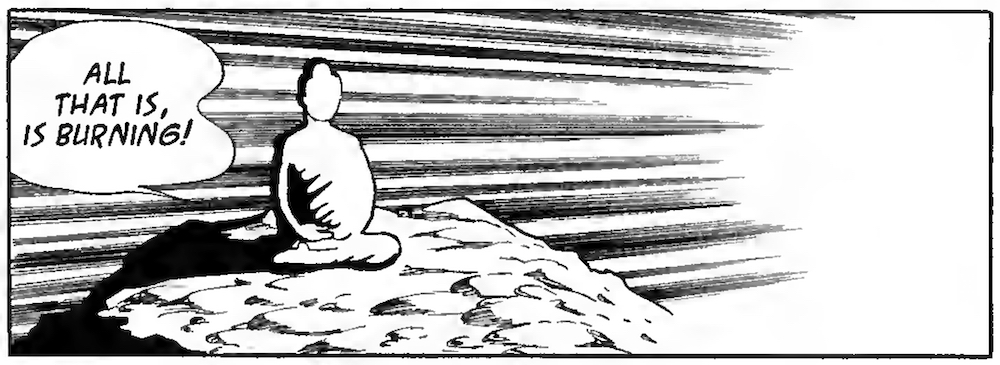

Sid’s mashup toys in Toy Story are a clear example of the creative-destructive processes underlying cultural innovation.

I often find it funny when and how an idea for something comes to mind for me. It never seems to be when I sit down and try to come up with something to create or write. The ideas I like the most usually suddenly hit me at the most unexpected, and certainly not sought after, times. Like while I’m literally contorted on my back, halfway through a yoga flow.

Yeah.

Granted, there was a direct connection to the bedtime story I was reading with my kids an hour or so before. They have a Pixar storybook filled with abridged versions of the films, and we restarted it earlier that night. It’s in order of release, so the first one was Toy Story (1995). Sid Phillips’ seemingly unhinged toy-destructive behavior is only glossed over in the storybook, but thinking about it afterwards triggered something I had never really considered: Sid’s questionable hobby is actually noticeably creative, and it’s also a clear example of mashup (more on that term here).

The first time we see Sid, of course, he’s not exactly eloquently participating in some sort of combinatory cultural practice or pointedly critiquing consumerism through his remix of mass-produced items. He’s blowing up a toy in his backyard – a Combat Carl, to be exact. As Rex explains to Buzz Lightyear, “he tortures toys, just for fun.” But Sid doesn’t refer to what he does as torture (even if blowing up an action figure and burning Woody’s forehead later with a magnifying lens certainly seem to fit the bill). Though he doesn’t refer to it as mashup either. They’re operations, to which his sister’s Janie doll and an unnamed pteranodon can certainly attest. But there’s also a difference between one of Sid’s so-called operations and the demolished toys littering his backyard that he’s all but completely annihilated.

One of the first mashed up items we see in Sid’s bedroom is his doll-part-filled lava lamp. And after the Janie-Dactyl operation, we encounter his other, previous creations. Fans seem to refer to these as “mutant toys” online, but I think “mashup toys” not only sounds less pejorative, but is also a far more accurate label.

First, we have Babyhead: a baby doll head with a missing eye attached to a spider-like body constructed out of erector set pieces (which was such a fun kit growing up, I’ve got to admit!). Then, let’s see, we’ve got Jingle Joe (a Combat Carl head affixed to the bottom part of a Melody Push Chime with a Mickey Mouse arm nailed to the side), Legs (a pair of doll legs attached to a fishing rod and reel), Ducky (a duck PEZ dispenser inside of a baby doll torso with a suction cup base on a spring), Rollerbob (the upper half of a pilot action figure mounted to a mini skateboard), Rockmobile (an insect head controlling a steering wheel attached to the headless and legless torso of a Rocky Gibraltar action figure), Pump Boy (a yellow convertible car with baby doll arms instead of wheels), Jack In The Box Hand (a green monster hand on the spring in a jack-in-the-box), and The Frog (a one-armed wind-up frog with a monster truck wheel in place of one of its original, smaller wheels).

Sure, calling these “mutant” toys would fit with the perspective that they have clearly been corrupted to some degree. They certainly aren’t the same as they were prior to their operations. But what about the opportunities and abilities these toys now have because of that change in form and composition? Has such a corruption or destruction of a previous state completely ruined them? Or has it resulted in something new, unique, and full of different sorts of possibilities?

Let’s pause for a quick refresher before answering that question.

There’s Buzz’s detached arm that’s re-affixed by the mashup toys within seconds. We see that the Janie-Dactyl operation was reversed by them as well. Legs was able to remove a vent cover with the rod’s hook and then lower Ducky down out of the ceiling by the front door (and then quickly pull back up with The Frog in tow). Ducky was able to climb down the side of a wall with its suction cup. Pump Boy used its arms to wind The Frog. Babyhead was able to support both Rockmobile and Jack In The Box Hand so that the former could lift the latter, which used its spring-loaded hand to grab and turn the doorknob to Sid’s bedroom door. Ducky was able to use its arms to lift out a light bulb fixture, ring a doorbell, and grab The Frog. And the mini skateboard was able to be directed and steered by Rollerbob (i.e., on its own).

Those certainly sound like new, unique, and different possibilities to me. And I think it’s safe to say that Woody’s escape-and-rescue mission at the end of the film wouldn’t have been successful without those new abilities either. In other words, it was only a success as a result of the toys in Sid’s room having been remixed. The toys’ destruction, then, led to the creation of something filled with novelty and exciting potential.

There’s a fitting term that comes to mind here as well, which is occasionally applied to other areas of society and culture outside of its initial context in economic theory: creative destruction. It’s typically linked to the political economist Joseph Schumpeter and his understanding of the process of economic structural destruction, which necessarily results in the creation of new economic structures. But other economic theorists, such as Tyler Cowen, more broadly locate the connection between creation/creativity and destruction/corruption throughout culture beyond economics; see his Creative Destruction: How Globalization Is Changing the World’s Cultures (2002) for more on this – especially in terms of cultural exchange. Daniel Berman applies the concept to an analysis of photography, photomontage, and collage, pinpointing the ability of “the modern day ensembler” to simultaneously “destroy and create meaning in the same stroke.” Without clear referents in repurposed works, prior meaning is destroyed, he argues. But one of his main points – and what I’m more specifically picking up on with remix processes in general and Sid’s mashup toys in particular – is that new meaning, functionality, and purpose emerge in such instances, resulting in the “destruction of one type of significance and the simultaneous creation of another.”

And I think it’s pretty clear that’s what has taken place on the workbench in Sid’s dingy room. But the point here is that this is how remix processes work anyway: amid the reassemblage of sourced material, within the destructive processes of deconstructing, there exists a creative impulse that guides and invigorates such cultural productions with an allure that dazzles our senses and draws us in across all sectors of society and culture.

Even among adolescents obsessed with fireworks.

It’s a shame that after four feature films in the franchise, we only got to see Andy’s (and Bonnie’s) wholesome development and relationship with the main cast of toys. Somewhere in that Pixar-created world, I’d like to believe Sid has been revolting against consumerism and corporate structures by subverting their mass productions and showing the world that other possibilities exist outside of the parameters of what’s being dictated by those who appear to be in charge.

Then again, there’s a pretty good chance he never touched another toy again after Woody presumably scared him straight.

At least we get a plastic spork with googly eyes, a blue wax stick mouth and red wax stick unibrow, popsicle stick and clay feet, and pipe cleaner arms and hands in Toy Story 4 (2019). So I guess in the end, as a sort of nod to Sid’s work years earlier and a subtle reminder of the destructive qualities underlying creation, I’ll take that over nothing: a unique repurposing of material that literally brings life to a new composite form…a creation that is far more than just disposable bits and pieces, and most definitely not trash.

Images from Toy Story and Toy Story 4 via Walt Disney Pictures and Pixar Animation Studios 1995 and 2019.