Buddhist philosophy and punk ideology probably don’t come across at first glance as complementary models for attaining a life without suffering. But they both advocate principles that demand the raising of one’s fists to put an end to an unsatisfying, oppressive, and cyclic existence in very similar ways.

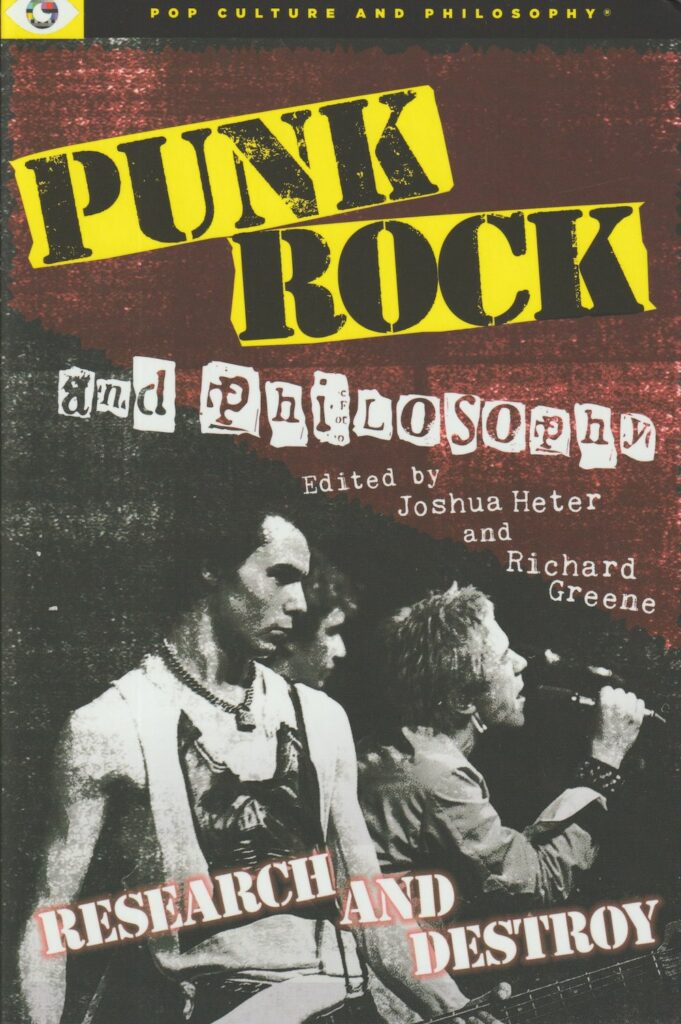

I recently contributed a chapter to a new volume in Carus Books’ Pop Culture and Philosophy series: Punk Rock and Philosophy: Research and Destroy. “Close Your Eyes, Breathe, and Stick It to the Man” is about the intersection between punk ideology and Buddhist philosophy. Now, I know what most prospective readers are probably thinking when they hear that: “Buddhism and punk? Come on. Get real.” But they both advocate principles that demand the raising of one’s fists to put an end to an unsatisfying, oppressive, and cyclic existence in very similar ways. This isn’t an entirely new notion either. Brad Warner, for instance, has been teaching and writing about Buddhism from a similar perspective since the early 2000s, and Noah Levine uniquely brought Buddhist thought and punk sensibilities to addiction recovery shortly after. That sort of initial trend in a Buddhist-punk coalescence served as the foundation for my chapter.

The chapter opens with a brief recap of Siddhartha Gautama’s departure from palace life because he simply couldn’t go on living surrounded by a cloud of ignorance, selfish desires, and corruption. “To give up a life of pleasure and comfort at a rather high social tier because you recognize how illusory, shallow, and fleeting such a life is, and that the ‘happiness’ it’s brought has only been at the expense of others’…that’s pretty damn punk,” I write (p. 245). But the broader connection between Buddhist philosophy and punk is that they both revolve around pointed calls for individual and social reform, a dismantling of hierarchical and unjust structures, and a change in perspective that amounts to nothing less than revolt.

The context and background for the Buddha’s early teachings is discussed in the first section, Sid, the Rebel…Not the Vicious, framing him as a revolutionary for his time, undiscriminating and unconcerned with caste. His message, succinctly conveyed via the four truths typically associated with it, was simple: if you want to wake up as well, “then sit down, shut up, and listen to what I discovered” (p. 246).

- Life is unsatisfactory

- It’s that way because of our incessant cravings and attachments

- We can put an end to that relationship

- That end is through a middle path between austerity and indulgence

His message wasn’t meant to be any more complicated than simply “a dedicated shift in perspective and mindful approach to the conditional world around us and learning how to understand what makes it tick and how that makes us suffer – learning how to raise our fists and make it clear that we won’t be held hostage by the cravings and attachments that keep us trapped in cyclic, unsatisfactory existence” (p. 247).

That first section closes with a review of one of the most important sets of moral principles in Buddhist philosophy: the five precepts. I have a little fun re-framing them as the five punk-cepts to suit the chapter, too.

- Slam into each other all you want, destroy what you need to, just don’t kill anyone

- If it doesn’t belong to you, don’t take it (although it might be okay to sabotage it…use your discretion)

- Sex is fantastic in a lot of ways and for a lot of different reasons, but remember, it can also be very emotive and invite quite a bit of vulnerability among those involved, so just be cool and take everyone’s feelings and satisfaction into consideration

- You can’t be trusted if you lie, so don’t be a coward, stand up tall and speak your mind

- Mind-altering drugs and booze cloud our judgments, decisions, and perceptions, and even though the experiences under their influence can often be incredibly enjoyable and relaxing, you should steer clear of using any of those substances so you can keep to that middle path without any hindrances or supposed “short cuts” to ending your pain and dissatisfaction

The next section, X Marks the Spot, emphasizes the importance of those moral principles, drawing correspondences between the precepts and the Straight Edge movement in punk subcultures (total abstinence from mind-altering substances and causal sex, often signaled by a drawn or tattooed X). This extreme sobriety focuses much more on the inner rebellion in order to not risk the loss of oneself in the theatrics of the outer rebellion. Criticisms about “short cut” methods for attaining some sort of enlightenment are also noted: “You don’t need a hit of acid. You don’t need to micro-dose any psylocibin. You don’t need to roll with some MDMA. You don’t need to go on some post-colonial escapade into the Peruvian jungle and participate in an ‘ancient’ DMT ceremony with a bunch of other tourists. Just sit down and shut up. Just close your eyes and breathe” (p. 248).

Critics argue that in very similar ways, such “short cut” methods are akin to what the Buddha put himself through during those years leading up to finding that comfy patch of grass under the Bodhi tree. They’re extreme and austere – certainly not the balanced median of opposing poles. And more importantly, they confuse that path in Buddhist thought as one with a final destination when the path itself is actually the goal: “Buddhist practice is no more about a quick fix to an existential problem than punk ideology is about escaping the societal ills they’re critiquing. It’s about lifelong reform and the marked journey that characterizes the challenges being leveled against that former ignorance and oppression” (p. 249).

This section is followed by one on direct action in both Buddhist thought and punk movements: Direct Meditative Action. In this section, I trace one of the major influential threads in the development of punk ideology to the Situationist International, and correlate its manifestation in punk subcultures as a call to disrupt and dismantle the misrepresentative reality of mainstream culture in favor of a more authentic existence to Socially Engaged Buddhist movements. Direct action in Buddhist practice is often characterized by the same types of radical social situations found among the Situationists and later punks, and the fact of the matter is that disrupting and subverting an oppressive social system and its structures is exactly what the Buddha was doing all along. The Buddha saw a world filled with suffering and discontent. “He inherently questioned it. His advocated path through it inherently challenged it. Why on earth would he require those listening to him to not embark on a similar journey of self-discovery and wisdom?” (p. 250). What we see today in Buddhist contexts amid various protests, boycotts, prison reform and humanitarian programs, campaigns for the lives and well-being of non-human animals, and environmental activism are just some of the ways these ideologies intersect – most radically, perhaps, among self-immolating monks like Thich Quang Duc.

In the final section, Sit Down, Shut Up, and Take a Look at It, I reiterate the personal imperative in Buddhist thought and punk ideology to examine, assess, and reorient our own lives: “No one is going to transform them for us. It’s up to us to take control and start understanding and working to reform the world we’re unsatisfied with and rebelling against” (p. 252). This really can’t take place if we aren’t surrounded by those who foster that inner rebellion either, which is why community is also important in both Buddhist and punk contexts. In Buddhist thought, we call this “right association,” and the point is that “we can’t possibly begin to start tearing down society’s stifling walls and shed the blinders if we’re surrounding ourselves with those who would make that much less possible – those who care very little for anything even remotely resembling the five punk-cepts, for instance” (p. 252).

I end the chapter with a call to heed such advice – taking control of our own lives and fostering that right sort of association – and telling readers that we might similarly start by “finding a nice, shady tree, taking a comfortable seat under it, and observing and appreciating everything around us” (p. 253). Because, truly, a clear mind and keen awareness of what’s going on inside and outside is what’s needed before getting up and marching off in total revolt yelling “Hey, ho! Let’s go!” as loud as we can.

The book is on sale now, so if you’re interested in reading my chapter in its entirety – and checking out what 30 other philosophers have to say about punk rock! – then I encourage you to grab a digital copy or support your local bookseller. Some of the contributors were recently on an episode of I Think, Therefore I Fan (Richard Greene’s co-hosted podcast), which can be accessed here.

Cover image courtesy of Carus Books 2022.